No changing of place at a hundred miles an hour will make us the one whit stronger, happier, or wiser. There was always more in the world than men could see, walked they ever so slowly; they will see it no better for going fast. The really precious things are thought and sight, not pace. It does a bullet no good to go fast, and a man, if he be truly a man, no harm to go slow; for his glory is not at all in going, but in being.

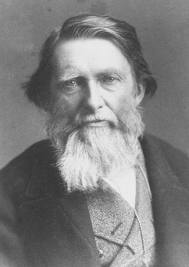

–John Ruskin, quoted in The Art of Travel by Alain de Botton

|

| John Ruskin |

Ruskin is one of the “guides” the author takes as a teacher in his study of this art of travel; this particular guide yearns to give us his students the tools to understand and possess beauty. Ruskin believed that we can only understand beauty by paying close attention to it, and that attempting to describe nature through writing or drawing was the surest way to focus the mind sharply enough.

On the topic of drawing Ruskin published two books in the 1850’s and gave lectures in London, but the point of his instruction was never to produce students who could draw well. He wanted to teach people to notice, and to “direct people’s attention accurately to the beauty of God’s work in the material universe.”

Right here is a good place to propose that we who believe in God the Creator also take as our teacher John Ruskin, rather than Mr. de Botton, because I doubt that we can learn much directly on the subject of beauty, especially on how to possess it, from a man who doesn’t understand that beauty, and in fact all that he possesses, are gifts from his Father God.

De Botton’s most recent book is Religion for Atheists, which he wrote from the conviction that a disbelief in God should not prevent atheists such as himself from making use of various aspects of the major world religions to better their lives. No doubt many professing Christians have a similar pragmatic outlook, and are missing out on the essence of the faith, Who is Christ Himself, the Bread of Life, the Glory of God the Father.

In musing about the beauty of God, I came upon a website with that title, featuring quotes from Jonathan Edwards. Many people have caught a bad impression of Edwards from those who speak of what they know not, but long ago I learned that the most frequent word in the preacher’s sermons was “sweet,” in reference to God and fellowship with Him. It’s not surprising that he had something to say about beauty as well. (The following paragraphs from Edwards were taken from his writings “The Mind” and “True Virtue” and bundled on the webpage with the added headings.)

God is Beautiful: “For as God is infinitely the greatest Being, so he is allowed to be infinitely the most beautiful and excellent; and all the beauty to be found throughout the whole creation, is but the reflection of the diffused beams of that Being who hath an infinite fulness of brightness and glory.”

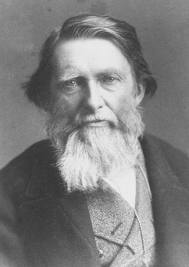

|

| Jonathan Edwards |

Beauty is a kind of consent or harmony: “[Beauty is] a mutual consent and agreement of different things, in form, manner, quantity and visible end or design; called by the various names of regularity, order, uniformity, symmetry, proportion, harmony, &c. . .”

“One alone, without any reference to any more, cannot be excellent; for in such case there can be no manner of relation no way, and therefore no such thing as Consent. Indeed what we call One, may be excellent because of a consent of parts, or some consent of those in that being, that are distinguished into a plurality in some way or other. But in a being that is absolutely without any plurality, there cannot be Excellency, for there can be no such thing as consent or agreement.”

Love is the highest kind of beauty: “The reason, or at least one reason, why God has made this kind of mutual agreement of things beautiful and grateful to those intelligent beings that perceive it, probably is, that there is in it some image of the true, spiritual, original beauty, which has been spoken of; consisting in being’s consent to being, or the union of spiritual beings in a mutual propensity and affection of heart. . . . And so [God] has constituted the external world in analogy to the spiritual world in numberless instances. . . . [He] makes an agreement of different things, in their form, manner, measure, &c. to appear beautiful, because here is some image of an higher kind of agreement and consent of spiritual beings.”

“When we spake of Excellence in Bodies, we were obliged to borrow the word Consent, from Spiritual things; but Excellence in and among Spirits is, in its prime and proper sense, Being’s consent to Being. There is no other proper consent but that of Minds, even of their Will; which, when it is of Minds towards Minds, it is Love, and when of Minds towards other things, it is Choice. Wherefore all the Primary and Original beauty or excellence, that is among Minds, is Love.”

God is beautiful because He is a Trinity: “As to God’s Excellence, it is evident it consists in the Love of himself; for he was as excellent before he created the Universe, as he is now. But if the Excellence of Spirits consists in their disposition and action, God could be excellent no other way at that time; for all the exertions of himself were towards himself. But he exerts himself towards himself, no other way, than in infinitely loving and delighting in himself; in the mutual love of the Father and the Son. This makes the Third, the Personal Holy Spirit, or the Holiness of God, which is his infinite Beauty; and this is God’s Infinite Consent to Being in general. And his love to the creature is his excellence, or the communication of himself, his complacency in them, according as they partake of more or less of Excellence and beauty, that is, of holiness (which consists in love); that is, according as he communicates more or less of his Holy Spirit.”

Jonathan Edwards did not have a perfect understanding of Trinitarian doctrine, but I am still very blessed by his giving glory to the Holy Trinity for Beauty, which of course can have its source and perfect demonstration no where else. For readings on the Holy Trinity I commend to you these pages.

|

| Above a storefront in Carmel, California |

Now, back to the subject of travel…I suppose no one wonders what all this beauty-talk has to do with our goings, because don’t we all like to look at beautiful things when we travel? And when we have to move on, we also like to keep something to take home with us. How to not lose everything of the experience of a new place?

De Botton suggests three ways that we often try: 1) Taking pictures with a camera, 2) imprinting ourselves physically, as in carving our names in a tree trunk and thereby leaving a bit of ourselves behind, 3) buying something, “to be reminded of what we have lost.” And none of these actions can have as much effect on the whole person as drawing.

In explaining his love of drawing (it was rare for him to travel anywhere without sketching something), Ruskin once remarked that it arose from a desire, “not for reputation, nor for the good of others, nor for my own advantage, but from a sort of instinct like that of eating or drinking.” What unites the three activities is that they all involve assimilations by the self of desirable elements from the world, a transfer of goodness from without to within. As a child, Ruskin had so loved the look of grass that he had frequently wanted to eat it, he said, but he had gradually discovered that it would be better to try to draw it: “I used to lie down on it and draw the blades as they grew — until every square foot of meadow, or mossy bank, became a possession to me.”

De Botton chronicles his own efforts to follow Ruskin’s advice, and when he attempts to draw a window frame in his hotel he finds that he had never actually looked at one before, in all its complexity of construction.

Many passages in the book also paint exemplary word-pictures, such as a paragraph on olive trees, of which the author at first “dismissed one example as a squat bush-like thing.” On closer consideration, with the help of Van Gogh’s art as well as Ruskin’s tools, he sees the trees in all their magnificence, telling us that “the taut silvery leaves give an impression of alertness and contained energy.”

There is another way that this description by de Botton follows Ruskin: in his anthropomorphizing of natural objects, attributing to them qualities that only humans or at least animals would actually have, and feeling that “they embody a value or mood of importance to us.”

In the Alps, he described pine trees and rocks in similarly psychological terms: “I can never stay long without awe under an Alpine cliff, looking up to its pines, as they stand on the inaccessible juts and perilous ledges of an enormous wall, in quiet multitudes, each like the shadow of the one beside it — upright, fixed, not knowing each other. You cannot reach them, cannot cry to them; — those trees never heard human voice; they are far above all sound but of the winds.”

My two-year-old grandson Scout is already a traveler following in Ruskin’s (and his mother’s) footsteps. He loves to hike and to stop and look at everything. On a recent outing he said, as he wandered off, “I’m going to climb up here, Mama, and the rocks will take care of me…”

That’s what I call the spirit of good old-fashioned traveling. Not the sort that Ruskin himself decried, in the 19th century: “Modern travelling is not travelling at all; it is merely being sent to a place, and very little different from becoming a parcel.”

When I am loaded on to a jet plane, I confess to feeling a bit like a parcel squeezed into a big crate of parcels. But Ruskin, and yes, even de Botton are helping me to be a more joyful and observant traveler, even if it’s only on a trip down the neighborhood footpath.

Before I had read just the small number of Ruskin’s words that are in The Art of Travel, I didn’t have the nerve to try my patience with drawing anything. But the man who wanted to teach me to notice has given me a vision of myself drawing a flower or a rock or a building. On my last car trip, I was even so bold as to pack into my bag a box of colored pencils.

Van Gogh was with his cypresses for quite a while, getting to know them. I have felt close to some particular trees over the course of my life, starting with a pear tree outside my back door, which for some reason made enough of an impression on my five-year-old mind that it remained the only thing I remember from that house’s yard.

Van Gogh was with his cypresses for quite a while, getting to know them. I have felt close to some particular trees over the course of my life, starting with a pear tree outside my back door, which for some reason made enough of an impression on my five-year-old mind that it remained the only thing I remember from that house’s yard.