![]() “The intimate darkness of our most precious cognitive organ constantly reminds us – whether we like it or not – that the “inner” content of any human is never absolutely available to our cognitive powers. The most powerful among the senses, thus, recognizes the deepest human cognitive powerlessness precisely during the encounter with the most powerful sense organ of another human being. However carefully we approach or analyze it, the unique personal existence of every human always stays partly hidden in the darkness of the unknowing.

“The intimate darkness of our most precious cognitive organ constantly reminds us – whether we like it or not – that the “inner” content of any human is never absolutely available to our cognitive powers. The most powerful among the senses, thus, recognizes the deepest human cognitive powerlessness precisely during the encounter with the most powerful sense organ of another human being. However carefully we approach or analyze it, the unique personal existence of every human always stays partly hidden in the darkness of the unknowing.

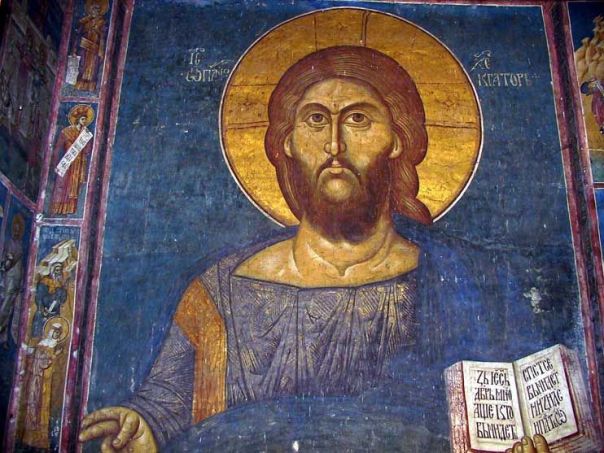

“And this is most expressively manifested when we encounter the small black dot that is the pupil of the eye. At this place we truly do “enter into the human soul,” but at the same time –confusingly and paradoxically – we realize that we cannot enter it. In this kind of darkness, we can get lost and go crazy, or feel warm and safe – for the same reason: because we cannot possess what it reveals/hides. This darkness can be scary or the most welcoming place in the world for the very same reason: because, herein, we recognize the utmost freedom of the human being.

“Through the encounter with the pupil of another human being, we fall directly into the other’s personal infinity, which can never be fully attained – even if our faces are only a few centimeters from each other. Experiencing this kind of infinity, finally, becomes the cognition of the utmost human freedom – freedom that does not depend even on itself.”

I added paragraph breaks to this excerpt from an article by Todor Mitrović from the Orthodox Arts Journal, on “The Epiphany of the Eye.”

I found the author’s ideas fascinating, and convincing. I am not an artist, but I do gaze upon icons quite a bit. When I do, I am looking through the “window,” not caring to analyze what features of the image are having what effect on me. This article nonetheless does help me to better appreciate the whole phenomenon. The artistry of an icon is not the most important thing about it, but contributes to its beautiful effect on our souls, our deepening relationship to Christ through prayer.

Metropolitan Anthony Bloom:

Metropolitan Anthony Bloom: The quote is from the opening paragraphs of Michael Hanby’s article,

The quote is from the opening paragraphs of Michael Hanby’s article,