This post that is very fallish in more than one way, I am sharing again nine years later. It is about Lin Yutang, whose writings my late husband and I were reading aloud together, during the illness that was to end his earthly life only a few months later. Much of what I read during that period is very foggy in my mind at this point, and many of those and other books from the past keep calling me back, especially when I read my own reviews.

This post that is very fallish in more than one way, I am sharing again nine years later. It is about Lin Yutang, whose writings my late husband and I were reading aloud together, during the illness that was to end his earthly life only a few months later. Much of what I read during that period is very foggy in my mind at this point, and many of those and other books from the past keep calling me back, especially when I read my own reviews.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

If you like thought-provoking quotes as much as I do, you might sometime run across one by the eloquent Lin Yutang. I find that I did have a quote by him about autumn in my files, so that is probably how he came under my radar recently, long enough for me to decide to borrow his book The Importance of Living from the library. It was in the closed stacks, and looks old and Chinese. But as Samuel Butler said, “The oldest books are only just out to those who have not read them,” and for me, Lin Yutang is definitely a new and exciting discovery.

I expected a small book of proverbs, perhaps, but The Importance of Living is a large conversational and philosophical treatise that I won’t be able to read in bed. I may have to buy a copy, because in the very first paragraph of the preface I found beautifully written lines that drew me in to his mind and his ruminations:

to read in bed. I may have to buy a copy, because in the very first paragraph of the preface I found beautifully written lines that drew me in to his mind and his ruminations:

“Very much contented am I to lie low, to cling to the soil, to be of kin to the sod. My soul squirms comfortably in the soil and sand and is happy. Sometimes when one is drunk with this earth, one’s spirit seems so light that he thinks he is in heaven. But actually he seldom rises six feet above the ground.”

I opened the book randomly in the middle and there, also, his words were worth thinking about as poetry or motivational talk. Did someone very gifted translate the works of this Chinese man? No, he wrote in English in such a graceful way that it is pure joy to read him aloud.

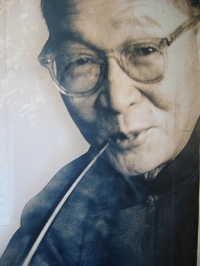

Lin Yutang was born in China in 1895 of Chinese Christian parents. His father was a pastor and a very progressive, forward-thinking man who made sure that Lin learned his Bible stories and went to the schools that produced the best speakers of English. He eventually got a degree from Harvard and another from Leipzig University.

I began to read The Importance of Living aloud with Mr. Glad. I usually do the reading because I enjoy it more than he does, and I immediately noticed the easy flow of Lin’s prose and the equally smooth progression of ideas. Everything he says makes perfect sense given his worldview in 1937, and at that time he was no longer a Christian.

What happened? Mr. Glad and I were very curious, because we had information Lin didn’t have at the time; we knew that later in life he would return to the faith and live to write about it, in his book From Pagan to Christian. So we stopped reading Importance and started in on the book about his spiritual journey that he wrote about 20 years later.

Putting together what he says in the relatively little we have read of him so far, I can tell you this about Lin’s first change of mind: As soon as he came of age to notice, he realized that he had not received the usual Chinese philosophical or literary heritage, much of which was typically learned through the theater; the theater was forbidden to Lin and his siblings who were in some ways raised as Puritans. He hadn’t taken the time to learn to write beautiful calligraphy, either, so he found that he was by Chinese standards completely uncivilized. At this point the one very Chinese thing he did know was intense shame.

He felt he had to go back and learn to be an authentic Chinese man, and having learned as a child the diligence and study habits of a Puritan, he did a very thorough job of learning Chinese philosophy and literature, not to mention a stunningly broad understanding of Western culture. This knowledge base combined with the ability to think and write about all that he has figured out — or is figuring out, as the story evolves — makes him fascinating to me.

We haven’t progressed very far in either of these books, but having this articulate author “friend” to explain Chinese culture and history to me from the inside has given me an interest in that part of the world that I have always lacked. So I hope to read more, and I expect to have more to share. But for now, I’ll close with his quote from My Country and My People about the  seasons of the year.

seasons of the year.

“I like spring, but it is too young. I like summer, but it is too proud. So I like best of all autumn, because its tone is mellower, its colours are richer, and it is tinged with a little sorrow. Its golden richness speaks not of the innocence of spring,nor the power of summer, but of the mellowness and kindly wisdom of approaching age. It knows the limitations of life and is content.”

This meditation seems to me an expression of a perspective that could be both Chinese, as he felt at the time, and truly Christian. I’m looking forward to reading more of the kindly wisdom of Lin Yutang.

“I realized that a crisis of limits is a crisis of culture, and a crisis of culture is a crisis of spirit. Every living culture in history, from the smallest tribe to the largest civilization, has been built around a spiritual core: a central claim about the relationship between human culture, nonhuman nature, and divinity. Every culture that lasts, I suspect, understands that living within limits—limits set by natural law, by cultural tradition, by ecological boundaries—is a cultural necessity and a spiritual imperative. There seems to be only one culture in history that has held none of this to be true, and it happens to be the one we’re living in.”

“I realized that a crisis of limits is a crisis of culture, and a crisis of culture is a crisis of spirit. Every living culture in history, from the smallest tribe to the largest civilization, has been built around a spiritual core: a central claim about the relationship between human culture, nonhuman nature, and divinity. Every culture that lasts, I suspect, understands that living within limits—limits set by natural law, by cultural tradition, by ecological boundaries—is a cultural necessity and a spiritual imperative. There seems to be only one culture in history that has held none of this to be true, and it happens to be the one we’re living in.” Volume 3 of Poem A Day, and it was by a poet I hadn’t read before, Siegfried Sassoon. I’m very glad to have discovered him. He is famous for his war poetry, and anti-war poetry, during and after The Great War.

Volume 3 of Poem A Day, and it was by a poet I hadn’t read before, Siegfried Sassoon. I’m very glad to have discovered him. He is famous for his war poetry, and anti-war poetry, during and after The Great War. is own poem, “The Power and the Glory,” on the

is own poem, “The Power and the Glory,” on the