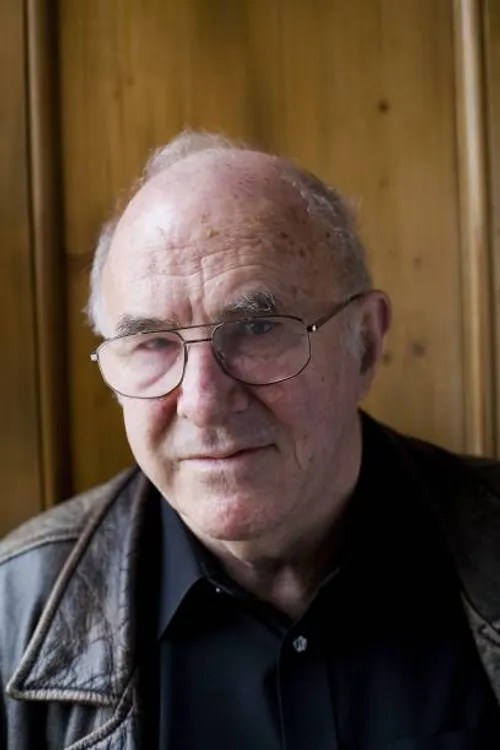

A few years ago I posted a poem by Clive James, the title poem “Sentenced to Life,” from the collection written after he became ill, and he began to consider his life from the perspective of a dying man. When I opened that book again recently I immediately was taken by another reflective poem with similar themes.

Reportedly James maintained confidence to the end that there is no afterlife, but I suspect he was cured of that delusion as he was crossing over. He did realize and admit publicly that he had been a “bad husband” (by long infidelity) and he regretted it. In his poems he compares his years of strength, the exciting years of his life, with the last decade when he was facing death, and he judges the recent, shorter season to be the time during which he was restored to sanity by facing the truth about himself.

LANDFALL

Hard to believe, now, that I once was free

From pills in heaps, blood tests, X-rays and scans.

No pipes or tubes. At perfect liberty,

I stained my diary with travel plans.

The ticket paid for at the other end,

I packed a hold-all and went anywhere

They asked me. One on whom you could depend

To show up, I would cross the world by air

And come down neatly in some crowded hall.

I stood for a full hour to give my spiel.

Here, I might talk back to a nuisance call,

And that’s my flight of eloquence. Unreal:

But those years in the clear, how real were they,

When all the sirens in the signing queue

Who clutched their hearts at what I had to say

Were just dreams, even when the dream came true?

I called it health but never stopped to think

It might have been a kind of weightlessness,

That footloose feeling always on the brink

Of breakdown: the false freedom of excess.

Rarely at home in those days, I’m home now,

Where few will look at me with shining eyes.

Perhaps none ever did, and that was how

The fantasy of young strength that now dies

Expressed itself. The face that smiled at mine

Out of the looking glass was seeing things.

Today I am restored by my decline

And by the harsh awakening it brings.

I was born weak and always have been weak.

I came home and was taken into care.

A cot-case, but at long last I can speak:

I am here now, who was hardly even there.

-Clive James

That made me think, maybe the line I didn’t get refers to the fact the narrator has come to realize, that “he” was not going to be around indefinitely, and that the loss of him would be incredibly painful. It’s the sort of intelligence that sinks deep into the soul, where the struggle to comprehend it continues indefinitely. Now, if she could go back, she would not be the same person, and the kind of knowledge she would take back to the past would be truly too much to bear in that “present.” It isn’t given to us humans to skip back and forth through time, which is a good thing, because just reading this poem demands more of my mind than is comfortable. Most of us can barely attend to the present, and excessive theorizing can be a sad waste of our hours.

That made me think, maybe the line I didn’t get refers to the fact the narrator has come to realize, that “he” was not going to be around indefinitely, and that the loss of him would be incredibly painful. It’s the sort of intelligence that sinks deep into the soul, where the struggle to comprehend it continues indefinitely. Now, if she could go back, she would not be the same person, and the kind of knowledge she would take back to the past would be truly too much to bear in that “present.” It isn’t given to us humans to skip back and forth through time, which is a good thing, because just reading this poem demands more of my mind than is comfortable. Most of us can barely attend to the present, and excessive theorizing can be a sad waste of our hours.