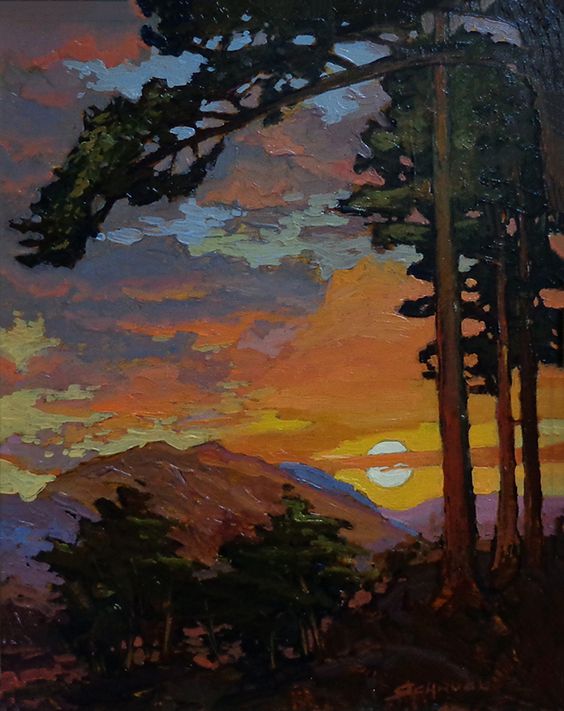

“Late one winter afternoon as I was walking to a class that I had to teach, I noticed the beginnings of what promised to be one of the great local sunsets. There was just the right kind of clouds and the sky was starting to burn and the bare trees were black as soot against it. When I got to the classroom, the lights were all on, of course, and the students were chattering, and I was just about to start things off when I thought of the sunset going on out there in the winter dusk, and on impulse, without warning, I snapped off the classroom lights.

“Late one winter afternoon as I was walking to a class that I had to teach, I noticed the beginnings of what promised to be one of the great local sunsets. There was just the right kind of clouds and the sky was starting to burn and the bare trees were black as soot against it. When I got to the classroom, the lights were all on, of course, and the students were chattering, and I was just about to start things off when I thought of the sunset going on out there in the winter dusk, and on impulse, without warning, I snapped off the classroom lights.

“I am not sure that I ever had a happier impulse. The room faced west so as soon as it went dark, everything disappeared except what we could see through the windows, and there it was—the entire sky on fire by then, like the end of the world or the beginning of the world.

“You might think that somebody would have said something. Teachers do not usually plunge their students into that kind of darkness, and you might have expected a wisecrack or two or at least the creaking of chairs as people turned around to see if the old bird had finally lost his mind. But the astonishing thing was that the silence was as complete as you can get it in a room full of people, and we all sat there unmoving for as long as it took the extraordinary spectacle to fade slowly away.

“For over twenty minutes nobody spoke a word. Nobody did anything. We just sat there in the near-dark and watched one day of our lives come to an end, and it is no immodesty to say that it was a great class because my only contribution was to snap off the lights and then hold my tongue. And I am not being sentimental about sunsets when I say that it was a great class because in a way the sunset was the least of it.

“What was great was the unbusy-ness of it. It was taking unlabeled, unallotted time just to look with maybe more than our eyes at what was wonderfully there to be looked at without any obligation to think any constructive thoughts about it or turn it to any useful purpose later, without any weapon at hand in the dark to kill the time it took. It was the sense too that we were not just ourselves individually looking our at the winter sky but that we were in some way also each other looking out at it. We were bound together there simply by the fact of our being human, by our splendid insignificance in face of what was going on out there through the window, and by our curious significance in face of what was going on in there in that classroom.

“The way this world works, people are very apt to use the words they speak not so much as a way of revealing but, rather, as a way of concealing who they really are and what they really think, and that is why more than a few moments of silence with people we do not know well are apt to make us so tense and uneasy. Stripped of our verbal camouflage, we feel unarmed against the world and vulnerable, so we start babbling about anything just to keep the silence at bay. But if we can bear to let it be, silence, of course, can be communion at a very deep level indeed, and that half hour of silence was precisely that, and perhaps that was the greatest part of it all.”

— Frederick Buechner

First read on Bologna.

I don’t know who all will be in my class when my parish’s church school program begins again next month. But I think I know what I’ll be teaching, and it includes gleanings from this book that I haven’t read yet, With Pain and Love for Contemporary Man. The arrangement of our classes and students and how and where they will meet is one more realm of decisions that has been affected by the coronavirus situation, and that is why I didn’t know until this week to get busy and start reading; I had expected to be using a different curriculum.

I don’t know who all will be in my class when my parish’s church school program begins again next month. But I think I know what I’ll be teaching, and it includes gleanings from this book that I haven’t read yet, With Pain and Love for Contemporary Man. The arrangement of our classes and students and how and where they will meet is one more realm of decisions that has been affected by the coronavirus situation, and that is why I didn’t know until this week to get busy and start reading; I had expected to be using a different curriculum.