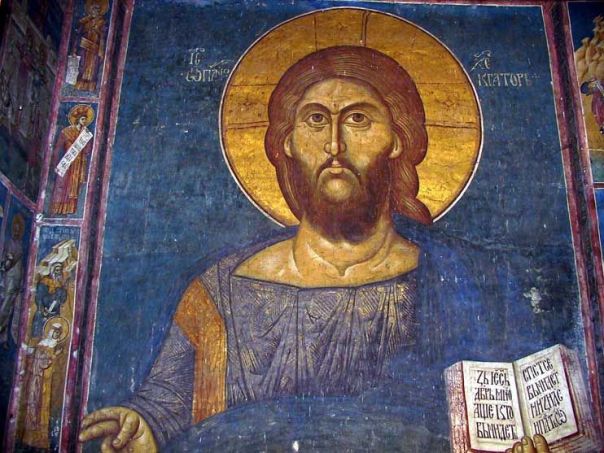

For it is the God who commanded the light to shine out of darkness, who has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ.

-II Corinthians 4:6

My priest mentioned in a homily recently that the verse above was his favorite; of course that made me pay close attention to it. Soon afterward I read an article by the iconographer Aidan Hart, “Lighting in Orthodox Churches: Liturgical Principles and Practical Ideas,” which has kept me thinking on this Light … and I’m certain I could benefit from further meditation on Hart’s ideas — because they flow from the truth that Christ Himself stated, that He is The Light of the World.

How do we reflect this reality symbolically when choosing physical lighting for our churches? And how might lighting help us to worship or distract us? If any of these questions is interesting to you, you might like to read the whole article, which I have linked above and below. Or skip the text and look only at the more than two dozen photographs of most beautiful churches and monasteries — and one mosque — illustrating the principles that Hart discusses. I especially loved the photo showing alabaster windows such as this one:

Hart reminds us that “The Church is ultimately a community of persons and not a building.” It follows that “Its light should illuminate the personal rather than the abstract.” He compares the needs of monasteries to those of parish churches, and The Blue Mosque to Hagia Sophia. The pros and cons of natural light, candles, oil lamps and electric lights are discussed; he explains how an environment with quiet light can help us to “learn the art of stillness, watchfulness, interiority.”

I’ll close with one paragraph that is rich with theological principles worth musing on, and leave you to click on the link for the whole article:

The second century neo-Platonist Plotinus wrote that “beauty is symmetry irradiated by life”. This was interpreted by the Byzantines as symmetry irradiated by light, for light was regarded an image of divine, animating and transfiguring life. But this Byzantine aesthetic of moving rather than static light was ultimately rooted in Trinitarian theology. The uncreated light of divine love is One, but it is also dynamic, moving within the Trinity and moving down to creation. Of course the term moving is a human concept and is ultimately inapplicable to God, who has no need to move from place to place. But the term is applicable inasmuch as it reminds us that God is not a single monad, that God is love because He is Three. Christian beauty is therefore rooted in relationship rather than an abstract and static ideal. And this can be reflected in church lighting.

-Aidan Hart, “Lighting in Orthodox Churches: Liturgical Principles and Practical Ideas”