AT UNIVERSITY

Puritans reckoned the cadavers

in Anatomy were drunks off the street;

idealists said they were benefactors

who had willed their bodies to science,

but the averted manila-colored

people on the tables had pinned-back

graves excavated in them

around which they lay scattered in the end

as if exhumed from themselves.

-Les Murray

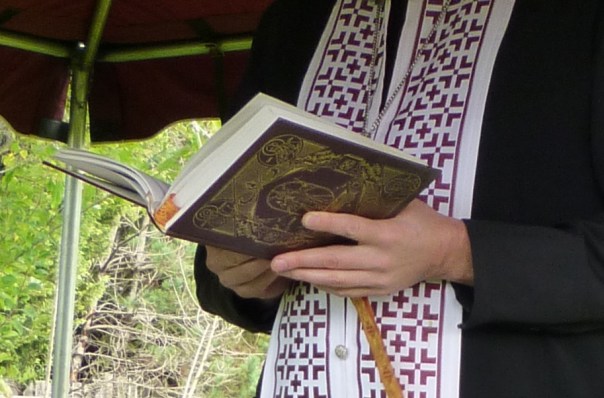

This month marks ten years since my husband’s departing from his earthly life, which leads me to meditate again on this topic. And today is one of the Memorial Saturdays we Orthodox have during Lent:

“Saturday is the day which the Church has set aside for the commemoration of faithful Orthodox Christians departed this life in the hope of resurrection to eternal life. Since the Divine Liturgy cannot be served on weekdays during Great Lent, the second, third, and fourth Saturdays of the Fast are appointed as Soul Saturdays when the departed are remembered at Liturgy.” (OCA)

Les Murray’s poem recognizes something about human beings that our modern consciousness rarely grasps: the unity that exists between soul and body, and the brutality of violating the physical aspect of a fellow human.

Les Murray’s poem recognizes something about human beings that our modern consciousness rarely grasps: the unity that exists between soul and body, and the brutality of violating the physical aspect of a fellow human.

Father John Whiteford writes that sometimes,

“…you will hear people say that the deceased is not in the coffin but with Christ, for example. However, if a person dies in Christ, their souls will be with Christ, but until the general resurrection, their body remains a part of them that will one day be reunited with their souls (though their body will be transformed) — and as such, the soul apart from the body is not the whole person (2 Corinthians 5:1-5).

If you are interested to know more about the Orthodox perspective on end-of-life issues, you might check out the Ancient Faith podcast “A Christian Ending” from Deacon Mark Barna, who has also co-authored a book by that title. Episodes of the podcast include: “Understanding Death,” “Cremation,” and “Preparing the Body for Burial,” and about a dozen more.

In the wholeness of Orthodox vision and practice, “…death is a change, but not an end. That which we see, the body, remains important and worthy of honor. A funeral, the service of remembrance, is a sacramental gathering in the presence of God. The body is honored, even venerated. The life of remembrance, eternal remembrance, begins.”

-Father Stephen Freeman, “A Secular Death”

It’s New Year’s Day according to our liturgical calendar, and special prayers for God’s blessing were included in our service this morning. What better time could there be for thinking about progress… or would devolution and even defeat be more realistic? I happened to read this passage today (I didn’t hear it in church) and just realized how it is connected, sort of. From a letter written by the Apostle Paul to his coworker Timothy:

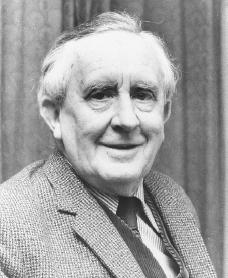

It’s New Year’s Day according to our liturgical calendar, and special prayers for God’s blessing were included in our service this morning. What better time could there be for thinking about progress… or would devolution and even defeat be more realistic? I happened to read this passage today (I didn’t hear it in church) and just realized how it is connected, sort of. From a letter written by the Apostle Paul to his coworker Timothy: Father Stephen Freeman has written over the years about how this passage is in agreement with what J.R.R. Tolkien wrote in a letter many centuries later:

Father Stephen Freeman has written over the years about how this passage is in agreement with what J.R.R. Tolkien wrote in a letter many centuries later:

The Orthodox Church starts Lent off with the Vespers of Forgiveness, which all are strongly encouraged to attend, and to participate in, by asking forgiveness of everyone else in the church, one by one.

The Orthodox Church starts Lent off with the Vespers of Forgiveness, which all are strongly encouraged to attend, and to participate in, by asking forgiveness of everyone else in the church, one by one.

Father Stephen Freeman by his writing has been helping us for a long time, to understand how shame motivates our behavior, both good and bad. There is both healthy shame, which we are “hardwired” with, and toxic shame, which often has unhealthy ramifications down through the generations.

Father Stephen Freeman by his writing has been helping us for a long time, to understand how shame motivates our behavior, both good and bad. There is both healthy shame, which we are “hardwired” with, and toxic shame, which often has unhealthy ramifications down through the generations.