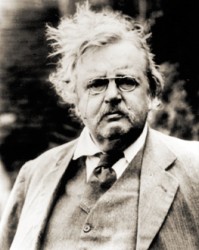

Today is the birthday of our dear friend G.K. Chesterton. He was born in 1874, which makes it 140 years since God gave him to the world. I’ve begun reading Chesterton’s autobiography two times, and it seems the least interesting of all his writings I’ve tried, because it doesn’t come naturally to the author to talk about himself. Much of what I read in the first chapters was about other people, perhaps well-known in his day but not to me.

Today is the birthday of our dear friend G.K. Chesterton. He was born in 1874, which makes it 140 years since God gave him to the world. I’ve begun reading Chesterton’s autobiography two times, and it seems the least interesting of all his writings I’ve tried, because it doesn’t come naturally to the author to talk about himself. Much of what I read in the first chapters was about other people, perhaps well-known in his day but not to me.

Chesterton liked people, as this clip from The Daily Herald in 1913 attests:

“Quite a swamping majority of the men and women I have met in my life I have liked very much indeed. I have never met that Ordinary Man who seems to bore some people so much. All the men I have met have been the most extraordinary.”

It’s a good thing that the man’s own personality and character shine through his writings, so that we may know how extraordinary he was and is. He is for me a stellar example of the sort of writer with whom a reader can have a rich relationship. You might think from looking at my blog today that he is my literary Significant Other, being the author of my one current Bedside Book and my theme quote, and the subject of this post. He isn’t even my favorite author, but I happen to have put his birthday on my calendar.

A few years ago, for the July/August 2011 issue of Gilbert Magazine, the editors asked some Chesterton experts, “What is the most Chestertonian book you’ve ever read that was not by G.K. Chesterton?” A couple of them thought there was nothing else that could compare.

But James Woodruff named The Wind in the Willows, which happened to be published the same year as Chesterton’s Orthodoxy, because it is “a celebration of the primal things Chesterton loved — Home and Friendship and Adventure — all suffused with a sense of wonder and lived out by characters who write poetry and go forth to battle and w ho eat and drink with right good will…”

ho eat and drink with right good will…”

Nathan Allen named The Abolition of Man by C.S. Lewis, “…because he deals with a lot of the issues that Chesterton cared about: education, the loss of a sense of a common culture, and so forth.” Other titles suggested were That Hideous Strength, also by Lewis; The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster; The Restoration of Property by Hilaire Belloc; The Restoration of Christian Culture by John Senior; and Pinocchio!

I wish I had a tidy way to take a few thoughts from and about this hero of mine and craft them into a fitting birthday tribute, but my skill and understanding don’t come near the level of my appreciation. [To demonstrate that fact: when I wrote that sentence I wasn’t yet aware that I had somehow moved his birthday forward 20 years. Ack! I think it’s fixed now.] Maybe after some more years — for his 150th? — I will do better than this mishmash. For today I will stop and let Chesterton’s own words from What is Right With the World convey the kind of attitude that has made him a favorite of mine and of ever-increasing numbers of readers:

“We are to regard existence as a raid or great adventure; it is to be judged, therefore, not by what calamities it encounters, but by  what flag it follows and what high town it assaults. The most dangerous thing in the world is to be alive; one is always in danger of one’s life. But anyone who shrinks from that is a traitor to the great scheme and experiment of being.”

what flag it follows and what high town it assaults. The most dangerous thing in the world is to be alive; one is always in danger of one’s life. But anyone who shrinks from that is a traitor to the great scheme and experiment of being.”

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, Mr. Chesterton!

(May 29, 1874-June 14, 1936)

ms that come my way: I don’t have whatever it takes to hear what is in that particular poem, and I can tell right away. On the other hand, maybe poetry books are the sort that I want to read when I am on the verge of exhaustion. A good poem can give at several levels, depending on my state of mind.

ms that come my way: I don’t have whatever it takes to hear what is in that particular poem, and I can tell right away. On the other hand, maybe poetry books are the sort that I want to read when I am on the verge of exhaustion. A good poem can give at several levels, depending on my state of mind. of book for less energetic times is a good cookbook, and The Joy of Cooking has been perfect for leisurely hours of perusal throughout my married life. Mr. Glad accommodated my desire for the 75th-anniversary edition, so I’ll be ready when that mood strikes.

of book for less energetic times is a good cookbook, and The Joy of Cooking has been perfect for leisurely hours of perusal throughout my married life. Mr. Glad accommodated my desire for the 75th-anniversary edition, so I’ll be ready when that mood strikes.