Yesterday when I wrote about my grief, I had started out to write a critique of the book I quoted from. Being my sweet self I had begun my essay not with what I didn’t like, but with something I appreciated about this grief counselor’s message. Immediately I realized that I wasn’t competent at that time to do anything requiring intellectual focus, because the quote helped me to see that I was scrambling to find my bearings without my “landmarks,” and that can consume all of one’s inner resources. So I wrote about that.

The fact is, I recommend the book with great reservations. It is Grieving Mindfully: A Compassionate and Spiritual Guide to Coping With Loss, by Sameet M. Kumar. The author presents several helpful metaphors like Landmarks and (traveling up) a Spiral Staircase, and important warnings about not trying to relieve the pain and depression with drugs, because that prevents you from doing the work of grieving.

All of those good things, and even the advice I didn’t find useful, could have been presented in a book half the length. The author is very repetitive, as though you are consulting him in his office for a year during which he has to reiterate the prescription every week.

Kumar is a clinical psychotherapist and grief counselor, and a Buddhist who credits the Dalai Lama with giving him the tools to find his career path and change his own life for the better. I mentioned some major concerns I had about his philosophy in my post on Changing Views, so if you like you can read them there; today I have thoughts on other aspects, though I haven’t the time, and maybe not the ability, to treat all of the problems I find.

I just read over that article and find that back then I unknowingly used a phrase that I hadn’t yet encountered in Kumar’s book: emotional energy. On the day I was writing about in August, I was surprised to find that I lacked emotional energy to do simple everyday tasks that should have been easy and even fun. But Kumar says that we should “use the tremendous influx of emotional energy that comes from experiencing loss to nurture life.” This labeling of the debilitating pain of grief as just another kind of power we can use to drive whatever activity we want is very odd, if not ludicrous.

Kumar writes a lot about compassion, and how we can turn the energy of our grief to compassion for others, but the book is short on concrete examples of what this looks like. From what I can tell, it means telling people, “Everyone suffers. Get used to it.” Can compassion be cold? Buddhists say yes.

Recently I read a brief account of a Buddhist who converted to Orthodox Christianity and became a monk on Mount Athos. He was questioned by a visiting priest about his reasons for leaving “such a great cultural tradition,” and he answered,

“Divine companionship!…In Buddhism, my Father, you are very very much alone. There is no God. Your entire struggle is with yourself. You are alone with yourself, with your ego. You are totally alone in this path. Great loneliness, Father. But here you have an assistant, a companion and a fellow-traveler in God. You are not alone. You have someone who loves you, who cares about you. He cares even if you don’t understand Him. You speak with Him. You tell Him how you feel, what you would have hoped for – there is a relationship. You are not alone in the difficult struggles of life and spiritual perfection.”

I can well understand this man’s natural desire to be with God, a Trinity of three persons in love and community, because it is a desire instilled in us by that God, who made us in such a way that we can’t be fully ourselves until we are pulled into that love relationship.

But Kumar says, “The acceptance of emotional hardship is the core of radical acceptance—simply being present with your feelings in the here and now, rather than longing for something different.“ [emphasis mine] Acceptance, I realize, is the path I am also on, but I think of it as being something like full contentment. My favorite word on contentment is in the book of Hebrews,

“Let your conversation be without covetousness; and be content with such things as ye have: for he hath said, I will never leave thee, nor forsake thee. So that we may boldly say, The Lord is my helper, and I will not fear what man shall do unto me.”

For many of us, being with God is something different and well worth longing for. To accept and be content with our lot is only proper and possible if we have found the One who will never leave us or forsake us. Divine Companionship is the very Presence of the Almighty God who has many names, each one speaking to one aspect of our heart’s longing.

This brings me to the last point of disagreement I will address, which is the form of mindfulness and meditation that is taught in this book. I don’t think it hurts to “simply be present with your feelings,” or to “come in full contact with yourself,” at least as a starting place. But I don’t believe that those encounters are likely in themselves to reveal “how capable we are of containing and healing the grief we carry.”

Jeffrey Brantley tells us in the Foreword that “…the benefits depend not upon trying to change anything, but instead mainly upon one’s willingness and commitment to reside in the present moment, while making room and becoming intimate with the texture of unfolding experience – whatever that is.”

And Kumar goes further in describing the intended results of this activity: “Mindful attention does not try to change what is happening. Instead, it reflects— accurately and precisely.” This idea of the accuracy  and precision of our thoughts that float by also seems to me lofty and unrealistic.

and precision of our thoughts that float by also seems to me lofty and unrealistic.

What we need is PRAYER, People! I am no expert on it, except to know assuredly that I need to do it, and that it is work. It doesn’t spontaneously generate from my random thoughts, but it comes from finding God in the present moment, in spite of our thoughts. Just google Orthodox and Prayer and you can find all the resources you need for getting started. My spiritual father told me early on to read anything that Anthony Bloom writes on the subject. It is in real prayer, in Divine Companionship, that we will find healing and contentment and a truly spiritual kind of energy, the Energies of God.

I attended a Holy Unction service with my goddaughter last night. Before the service proper our priest read an article on

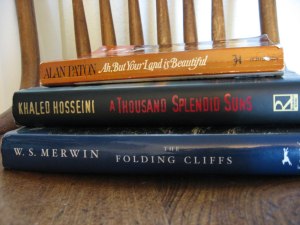

I attended a Holy Unction service with my goddaughter last night. Before the service proper our priest read an article on  ee books were at three corners of the globe. Obviously they were not part of any theme. So were there some ways they were alike? What made them all worth reading to the end, when so many books I’ve tried lately were not?

ee books were at three corners of the globe. Obviously they were not part of any theme. So were there some ways they were alike? What made them all worth reading to the end, when so many books I’ve tried lately were not?

when a good writer connects with the reader:

when a good writer connects with the reader: