“Three forces carved the landscape of my life. Two of them crushed half the world. The third was very small and weak and, actually, invisible. It was a shy little bird hidden in my rib cage an inch or two above my stomach. Sometimes in the most unexpected moments the bird would wake up, lift its head, and flutter its wings in  rapture. Then I too would lift my head because, for that short moment, I would know for certain that love and hope are infinitely more powerful than hate and fury, and that somewhere beyond the line of my horizon there was life indestructible, always triumphant.

rapture. Then I too would lift my head because, for that short moment, I would know for certain that love and hope are infinitely more powerful than hate and fury, and that somewhere beyond the line of my horizon there was life indestructible, always triumphant.

“The first force was Adolf Hitler; the second, Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin. They made my life a microcosm in which the history of a small country in the heart of Europe was condensed. The little bird, the third force, kept me alive to tell the story.”

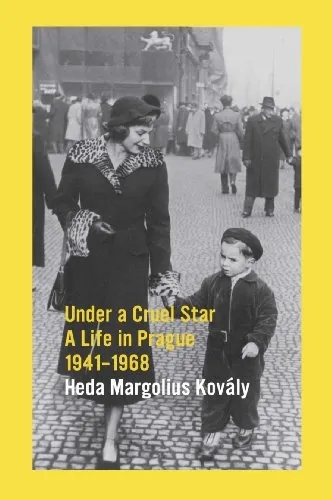

Those are the first two paragraphs of the book Under a Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968 by Heda Margolius Kovály, which I read last year. What a survivor that “little bird” helped the author and heroine to be, again and again; her story is gripping and intriguing in every way, and I highly recommend it. She survived Auschwitz, and near the end of the war managed to escape. She ran to her friends in Prague, but none of them dared take her in. The remainder of her story is very suspenseful, and demonstrates the strength of will and hope that continued to uphold her through the suffering and loss  under Communist rule.

under Communist rule.

An interview with Heda was recorded in 1980 for “Voices from the Holocaust,” which you can listen to here: Heda Kovály. The outline of her life is laid out in a transcript and episode notes. They are a good supplement to her book, but I’m very glad I learned her story first from her earlier, very personal telling of it.

Not long after reading Under a Cruel Star, I came across the poem below, which speaks of a place such as Heda’s little bird occupied — this hidden place from which help comes in the form of a song.

LACK OF FAITH

Yes,

even when I don’t believe—

there is a place in me

inaccessible to unbelief,

a patch of wild grace,

a stubborn preserve,

impenetrable,

pain untouched by the sleeping body,

music that builds its nest in silence.”

― Anna Kamieńska, Astonishments: Selected Poems

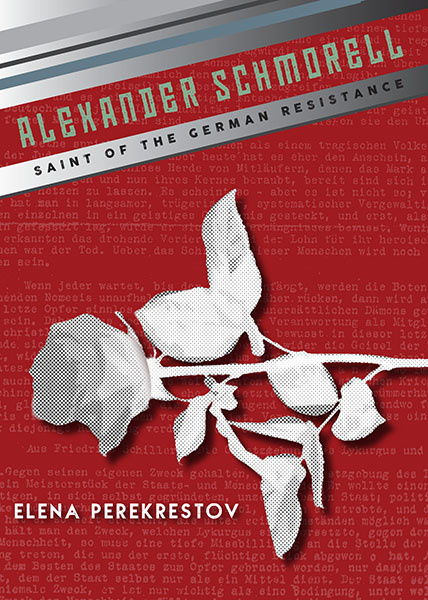

Scholl: The Final Days”) that I first heard of The White Rose, a non-violent youth resistance group formed in Munich in 1942.

Scholl: The Final Days”) that I first heard of The White Rose, a non-violent youth resistance group formed in Munich in 1942.