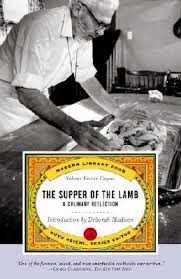

The book into which I am dipping to give you several tastes is Supper of the Lamb by Robert Farrar Capon. The title refers on one level to the four meals he will show us how to make, for eight people at each sitting, out of one leg of lamb. As I said in my first post, it’s not these recipes that most interested me about the book, but they form the loose structure around which the author gathers all his personality and wisdom.

He tells us that “Lamb for Eight Persons Four Times is not simply a recipe. It is a way of life.” A way that has us deliberately creating leftovers so that for most suppers we can use little bits of our meat and make it go a long way. I have a lot of experience with this kind of cooking, and I appreciate Capon’s undergirding philosophy, that there are times to feast, and they are not every day.

He has a term for the everyday: ferial eating. I found in the dictionary that it’s a church term for a weekday on which no feast is celebrated. Capon’s first principle for this ordinary type of eating is: Never serve anybody a whole anything. Because “appetite rises to meet food supply,” and we just don’t need to eat large amounts every day.

Every dish in the ferial cuisine, however, provides a double or treble delight: Not only is the body nourished and the palate pleased, the mind is intrigued by the triumph of ingenuity over scarcity — by the making of slight materials into a considerable matter.

I have to admit that in the days when our feasts were rare, it was easier for us all to stay slim and healthy. For several years now, cooking for only two people, I’ve probably been serving way too many whole items, and I also have so many leftovers from which to create more yummy meals that I hardly have enough cold storage for them. The type of lifestyle where the cook shops nearly every day and prepares what is fresh in the shops in that season seems to be what I should aim for.

Still, I very much appreciate that Capon introduces us early on to his idea of the creative and resourceful cook, who knows how to season and sauce her humble food so that it’s often more interesting and delectable than the festal roast.

Still, I very much appreciate that Capon introduces us early on to his idea of the creative and resourceful cook, who knows how to season and sauce her humble food so that it’s often more interesting and delectable than the festal roast.

Just tonight my man and I enjoyed for the second time (as I’d ended up with a big potful) a soup that was made according to these methods, using the leftover lamb roast from Christmas as well as the leftover liquid it was cooked in, which included a good amount of wine, with rosemary and garlic. Not too much meat was left, but I added some lentils and vegetables, and Mr. Glad could not help feeling it quite unfair that he should be eating such amazing food when so many people never get stuff like this. (The stew in the photo is from a previous and different ferial meal.)

Our author chef carves his (large) leg of lamb into parts to make first a stew, and then three other ferial meals, including a casserole with spinach, a stir-fry, and a soup. His recipe for stew includes an injunction against flouring the meat before browning it:

…it is the point at which nine tenths of the stews in the world go wrong. The trouble is that few cooks realize how long it takes to brown meat thoroughly….People who flour their meat and brown it in butter are entitled to their religion….I think it fair to note, however, that such people have never gotten around to browning meat. All they have done is darkened some butter and scorched a little flour. The meat inside remains untouched. Accordingly, their stews never know the savor of the true burnt offering; in their haste they settle for the dubious pleasure of eating charred wheat.

Unfortunately my mother taught me to flour my meat and it was only a few years ago that I learned better. RFC also gives advice about liquid:

A word about the liquid itself. Unless you are physically prevented from doing so, always use stock or wine, especially in a ferial stew. We are working here with an admitted minimum of meat. To add water to it is to strain it, to demand of it a cruel exertion, to have it arrive at the table worn out with overwork. This is no festal dish with enough meat in it to make meals for a week. This is a poor dish, whose meat is to be pitied and spared. Accordingly, any liquid that goes into it should be of a charitable and kindly sort…which knows how much more blessed it is to give than to receive. Stock then; not water. And, no matter what else, wine. A gallon of good California red in the kitchen closet will do more for your cooking than all the books in the world.

Capon has more opinions about wine, and the philosophy of meat-eating, “little invisible spooks” (Can you guess what those might be??), and the “higher session” of The Supper of the Lamb, and that is why I need a few more posts to share my gleanings. Coming soon!

The first post in this series is RFC is the man you need.