On Saturday I drove my out-of-town friend to the coast. We have several times made this trip when she is visiting her family for Thanksgiving. The weather was forecast to be sunny all day, which we received as a wonderful gift, though we are used to fog out there at any time of the year.

When we arrived it was truly a gorgeous day. No wind, and plenty of sunshine and blue skies. The long road to the parking lot next to the beach was closed to cars, with no explanatory signage. Maybe it was because of the king tides still happening, which make these already dangerous beaches even more so. But we were allowed to walk down, which just gave us more good exercise coming back, so that was okay.

Only about two dozen harbor seals were lying by the mouth of the Russian River. But throngs of gulls were coming and going above us, and then making a racket as they swam in huge flotillas of white specks on the river, the whole scene sparkling.

Suddenly, the fog arrived! Unexpected, but not surprising.

That’s how it goes on the North Coast.

After watching the seals and gulls for a while longer, Mother S. and I began our long, slower this time, walk back up to the car, and our long drive home again. We were well satisfied.

Moving on to this morning… When I was adding water to the fountain I heard a woodpecker up in the redwood tree in the neighbor’s yard behind mine. I rarely do hear those birds around here so it was a pleasant encounter, though I couldn’t get my eyes on him.

I did see a hummingbird checking out my new abutilon that is in a pot; I wonder if that is a flower that actually offers any drink to the hummers? Seems like they would have to fly upside down while drinking…

Today I cooked up the first batch of greens from the planting by the driveway. It’s convenient having them growing there, because I notice them at least several days a week when I get in and out of the car. These I picked Saturday morning, and stuck them in the fridge to wait a couple of days. Yum! The flowers are on either the Chinese broccoli or the kalettes; I got them mixed up. But they taste good so they went into the pot, too.

When Pathfinder was here he was looking at my olive trees that are growing in pots. One of them he gave me fifteen years ago, and the other I bought in a little pot at the grocery store a couple of years later. I also got them mixed up, because after years of careful pruning, they have the same shape, which they didn’t at first.

Pathfinder asked me what type of olive I had bought for myself, and I said it started with an “A.” That would be an Arbequina, he told me. And he knew that he had given me a Manzanillo; then he pointed out the different shapes of the olives that are right now on the trees. He knows the Manzanillo, which is this one with pointier fruits:

Which means that the Arbequina is this one:

I never noticed the difference before! They are on opposite sides of the path from each other, so I don’t see them closely at the same time. That’s my only excuse for my inattention, but it saddens me that I don’t know my beloved trees very well. Pathfinder cures olives, so he has an eye for them. And now I know them better.

The last unripe fruits to show you are my pineapple guavas. Last week I harvested six ripe ones from the ground under the bush. Today I searched, but no more had fallen, and even the largest of the hundreds still hanging on were hard. Probably few if any more will come of age; their mini climate is just not ideal for them.

At least the snapdragons are being beautiful along the front walk.

This week I’m joining quite a few people in the parish for a Thanksgiving dinner in our church hall. I’m bringing a large quantity of the famous Orange Yams, adapted from my mother-in-law’s recipe. I see that I’ve never shared that recipe here before, so I’ll try to remember to take a couple of pictures to go with a recipe to be posted later.

December is almost here… And then 2025 will be history!

We must breathe deeply and make the most of every day ❤

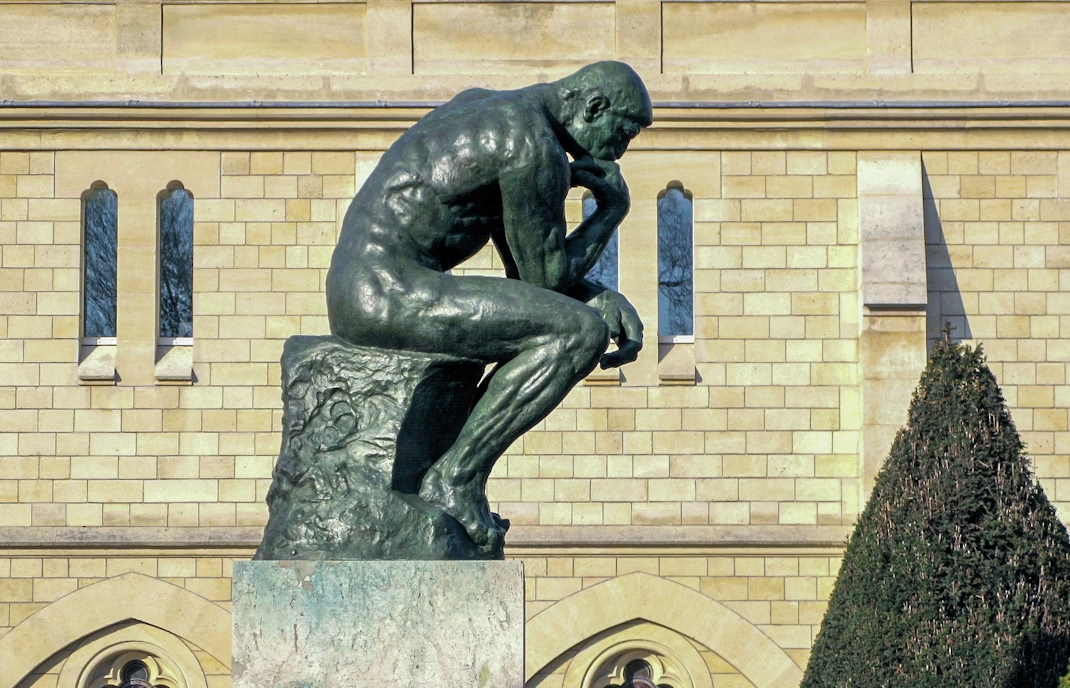

More and more I notice that people, including me, use the words brain and mind interchangeably; but they are not the same thing at all. No scientist has been able to find the mind in the brain. And when we are considering mind vs. heart, where is the heart exactly? As the Scripture says, “We are fearfully and wonderfully made.” The more researchers probe into the intricacies of the human body and its functions, the more complex we are found to be, the more questions emerge.

More and more I notice that people, including me, use the words brain and mind interchangeably; but they are not the same thing at all. No scientist has been able to find the mind in the brain. And when we are considering mind vs. heart, where is the heart exactly? As the Scripture says, “We are fearfully and wonderfully made.” The more researchers probe into the intricacies of the human body and its functions, the more complex we are found to be, the more questions emerge.