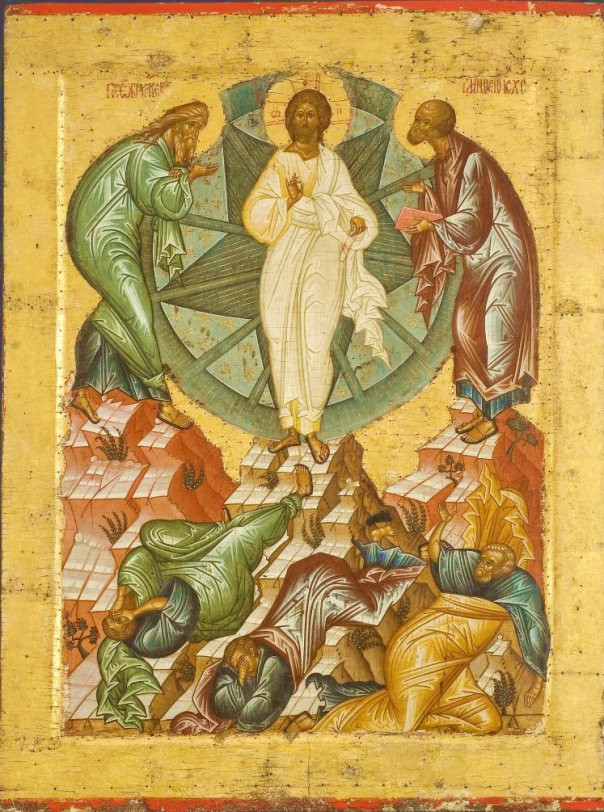

The poem below got me started thinking about mountains and their symbolism. I discovered a very long article on the subject, “The Transfiguration on Mount Tabor: The Symbolism of the Mountain,” which I don’t have time to read deeply, because as I type this draft, I’m in the midst of packing the car for five of us who will be in the mountains together by the time you read my post. I hope the article is not paywalled. It is a treatise on the subject going back millennia, opening with this from René Daumal:

“[The] summit touches the sphere of eternity, and its base branches out in manifold foothills into the world of mortals. It is the path by which humanity can raise itself to the divine and the divine reveals itself to humanity.”

The author examines traditions throughout the world, beginning in ancient times and concluding with thoughts on what The Mountain means for us Christians who are on a continuum with those 2,000 years ago. Here is one excerpt to help you know if you are interested in the subject from a scholarly perspective :

“In the traditional Hebrew and Christian understanding of the world, places are what they are by their teleology: it is not so much by the material or structural elements that they are recognized, but by their function. Things are what they are because of their purpose and their place in a web of relationships within reality which help create our own map of meanings. Therefore, it is very difficult to understand from a purely geographical (time-space) position where God dwells with regards to this or that mountain. For this reason, many physical mountains have been ‘the mountain of God’. There is only ‘one’, but it’s not confined to one geographical space-time location as we modern people understand it.”

I guess it’s obvious that I myself am interested, and I thought of printing this article to take with me to the high country, but I’m afraid I won’t have time to read it up there, either. My family and I will be too busy playing around our grandfather’s knees.

THE MOUNTAIN

The Mountain sat upon the Plain

In his tremendous Chair—

His observation omnifold,

His inquest, everywhere—

The Seasons played around his knees

Like Children round a sire—

Grandfather of the Days is He

Of Dawn, the Ancestor—

-Emily Dickinson

The quote is from the opening paragraphs of Michael Hanby’s article,

The quote is from the opening paragraphs of Michael Hanby’s article,

Today I’ve been tossing out most of my beloved Touchstone and Gilbert magazines, but not before I glance at notes I’d written to myself on their covers ten or more years ago, suggesting to my mind and pen (and keyboard) topics to muse and write about. I have accumulated several boxes of such periodicals, including cooking and gardening magazines as well, every issue containing provocative information and knowledge that I hoped to incorporate into my daily life, both the active and contemplative aspects.

Today I’ve been tossing out most of my beloved Touchstone and Gilbert magazines, but not before I glance at notes I’d written to myself on their covers ten or more years ago, suggesting to my mind and pen (and keyboard) topics to muse and write about. I have accumulated several boxes of such periodicals, including cooking and gardening magazines as well, every issue containing provocative information and knowledge that I hoped to incorporate into my daily life, both the active and contemplative aspects.