I stopped and snacked on a few blackberries along my walking path this week, and that made me think about my dear late husband. And I wondered, how long does one use the descriptor “late” to refer to the deceased? So I read about that here. And after I read, I wanted to call him my “swete and late amyable husbonde.”

I stopped and snacked on a few blackberries along my walking path this week, and that made me think about my dear late husband. And I wondered, how long does one use the descriptor “late” to refer to the deceased? So I read about that here. And after I read, I wanted to call him my “swete and late amyable husbonde.”

We are used to hearing that adjective attached to its noun, but I found it charming to read in Alexander McCall Smith’s novels of Botswana how people would simply state about someone who had died, “He is late.” You might think that the phrase refers to someone who has only recently died, but I can attest to the relative meaning of recently when we are talking about one’s lifelong partner.

A quote from this month’s New Yorker magazine, in the article about hospice worker Heather Meyerend, “The Threshold”, by Larissa MacFarquhar:

“People react differently to a death. Some cry, some are calm….Wives sometimes throw themselves on the body, weeping and grasping it, especially when the couple have been married forty, fifty, sixty years. ‘The Bible says, And two shall become one,’ Heather says. ‘It’s a wrenching that happens, a tearing, like a garment that’s being pulled apart.'”

Mr. Glad and I married when we were both 21, and soon moved from southern to northern California. Before we had even settled on what county we might live in, we were picking wild blackberries together, up in the redwood forests of Humboldt County. From then on it was a July tradition to search around the country roads or empty lots to gather enough for several pies and a few quarts of syrup as well. That’s how it happened that we formed the habit of his birthday pie.

As I’ve thought so much about my husband and our life together over the last year, Sheldon Vanauken’s book A Severe Mercy comes to mind, because it includes a lot about the death of his wife and his dealing with that. I didn’t like the book very much when I read it many years ago, because of the way the two of them seemed unswervingly self-absorbed as a couple; but one thing the grieving husband did tell about always stuck with me and made me ponder, long before I imagined myself in his position.

His wife’s nickname was “Davy,” and within days after her death he experienced the “flooding back to me of all the other Davys I had known. She had been in the year of her dying the Davy she had become — the Christian Davy of Oxford and since,” but he began to remember her at various times of their life together and even before, and to liken this process to what happens when you come to the end of a novel. You have been focused on each page and what the character is doing, who she is at that point in the story. Then you close the book and begin to grasp the meaning of it all from the first chapter on through.

When you are a hospice nurse, or the sole caregiver of a dying person, you have to focus on that day, that page of the life, to give all the love and attention you can. I hope it is possible for you to read the article I linked to above, about this particular nurse – if it becomes unavailable try googling her name – because the description of her work and ministrations is that of a saint. The author of the article follows her on her visits to several different homes and chronicles her interactions with the patients, and her wise assessments of the needs of the dying generally. The story of her own life shows how she was formed and guided by God into this realm that she seems imminently suited for.

When my husband was dying, our family didn’t need the hospice workers to help us with matters of the heart, but I appreciated Heather’s insight about such things as this:

When a patient was tormented and having a difficult time dying, or was hanging on despite no longer eating or drinking, Heather would ask, Is there someone you need to see? If a patient was preoccupied with someone he was resolved never to forgive, Heather might say that this unforgiveness was like bondage, and that if he forgave the person who had injured him that person would no longer be his jailer.

I thought that when I helped my goddaughter in her last days that the experience provided plenty of revisiting of the last months of my husband’s life, but reading about hospice care a year later is actually helpful. I’m less self-absorbed myself and can look back more calmly and see many reasons for thanksgiving in the last weeks and even hours.

One phenomenon that is mentioned in the article is how many people when they are in their last days seem to wait until they are alone before they let themselves “go.” One wife worried a lot about this when her husband was in hospice care, concerned that she might not be with him at that moment, and she was relieved when she was able to be by his side at the end.

I didn’t worry about it, but I would have preferred to be with my husband, and I was. Only from this vantage point does it occur to me that this was a gift from him to me and the daughters who were also there holding his hand, to let us accompany him all the way until the crossing over.

Whenever Heather entered a patient’s home for the first time, she knew that she was walking into a long, long, complicated story that she understood nothing about, a story that was just then reaching its final crisis.

Until today most of my own efforts to look back on my husband’s life have taken me far from last year’s final crisis, and by means of photos I’ve been helped to remember him at earlier stages in his life. But reading things he’s written is perhaps even more satisfying. I’ve just begun to sort through papers to find notes and creations that surprise me, that make me see the depth and complexity of the man whom I was mostly reading page-by-exciting-page all those years. We were living out our own novel, so to speak, and we were, as protagonists usually are, unknowing of what was going to be on the next page. But our Heavenly Father was the author, and He was making the ending very good, in spite of crazy things the characters might do or go through along the way.

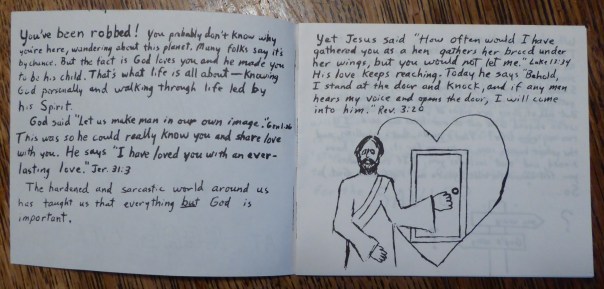

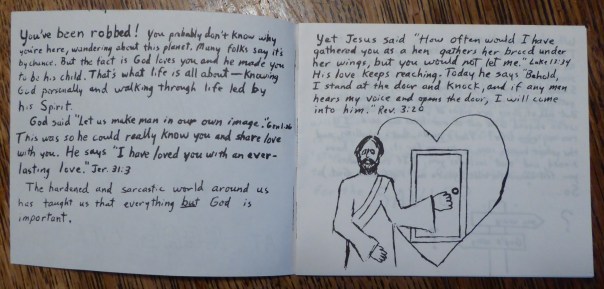

I had forgotten about this gospel tract that he created — was it in his 30’s? Unfortunately he didn’t put a date on anything I have dug up so far. In those days he did like to have some “literature” to give people he met, something they could read later on, and I imagine he found most such material too reductionist to be called The Gospel, so he had to make his own. The content of it tells of his foundation in Christ, and also of what he died knowing.

I had forgotten about this gospel tract that he created — was it in his 30’s? Unfortunately he didn’t put a date on anything I have dug up so far. In those days he did like to have some “literature” to give people he met, something they could read later on, and I imagine he found most such material too reductionist to be called The Gospel, so he had to make his own. The content of it tells of his foundation in Christ, and also of what he died knowing.

I miss my husband terribly. The grief ebbs and flows and is never the same, except for being always present. I’m glad I’ll be in this process for some time, of rereading my husband’s life and remembering more things to love him for, and be thankful. I’m loath to give up that berry pie tradition, so next week, on his birthday, I’ll be baking one again — even though I already know he will be late for the party.

Last year I spent quite a few hours sorting through photos of several generations of ancestors, my late husband’s family and mine, plus those of our own immediate family, children and grandchildren. I barely made a dent in the collections!

Last year I spent quite a few hours sorting through photos of several generations of ancestors, my late husband’s family and mine, plus those of our own immediate family, children and grandchildren. I barely made a dent in the collections!

Every baby coming into the world is a unique event, and my own feelings about births I’ve been present for have also been various. The group of people who have been appointed, as it were, to participate, each in her own way, bring all their personalities and prayers, and God is always present.

Every baby coming into the world is a unique event, and my own feelings about births I’ve been present for have also been various. The group of people who have been appointed, as it were, to participate, each in her own way, bring all their personalities and prayers, and God is always present.

I stopped and snacked on a few blackberries along my walking path this week, and that made me think about my dear late husband. And I wondered, how long does one use the descriptor “late” to refer to the deceased? So I read about that

I stopped and snacked on a few blackberries along my walking path this week, and that made me think about my dear late husband. And I wondered, how long does one use the descriptor “late” to refer to the deceased? So I read about that

I had forgotten about this gospel tract that he created — was it in his 30’s? Unfortunately he didn’t put a date on anything I have dug up so far. In those days he did like to have some “literature” to give people he met, something they could read later on, and I imagine he found most such material too reductionist to be called The Gospel, so he had to make his own. The content of it tells of his foundation in Christ, and also of what he died knowing.

I had forgotten about this gospel tract that he created — was it in his 30’s? Unfortunately he didn’t put a date on anything I have dug up so far. In those days he did like to have some “literature” to give people he met, something they could read later on, and I imagine he found most such material too reductionist to be called The Gospel, so he had to make his own. The content of it tells of his foundation in Christ, and also of what he died knowing.