It’s New Year’s Day according to our liturgical calendar, and special prayers for God’s blessing were included in our service this morning. What better time could there be for thinking about progress… or would devolution and even defeat be more realistic? I happened to read this passage today (I didn’t hear it in church) and just realized how it is connected, sort of. From a letter written by the Apostle Paul to his coworker Timothy:

It’s New Year’s Day according to our liturgical calendar, and special prayers for God’s blessing were included in our service this morning. What better time could there be for thinking about progress… or would devolution and even defeat be more realistic? I happened to read this passage today (I didn’t hear it in church) and just realized how it is connected, sort of. From a letter written by the Apostle Paul to his coworker Timothy:

“But know this, that in the last days perilous times will come: For men will be lovers of themselves, lovers of money, boasters, proud, blasphemers, disobedient to parents, unthankful, unholy, unloving, unforgiving, slanderers, without self-control, brutal, despisers of good, traitors, headstrong, haughty, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God, having a form of godliness but denying its power.

…Now as Jannes and Jambres resisted Moses, so do these also resist the truth: men of corrupt minds, disapproved concerning the faith; but they will progress no further, for their folly will be manifest to all, as theirs also was. But you have carefully followed my doctrine, manner of life, purpose, faith, longsuffering, love, perseverance, persecutions, afflictions, which happened to me at Antioch, at Iconium, at Lystra– what persecutions I endured. And out of them all the Lord delivered me. Yes, and all who desire to live godly in Christ Jesus will suffer persecution. But evil men and impostors will grow worse and worse, deceiving and being deceived.” (2 Timothy 3:1-13)

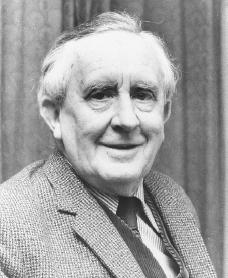

Father Stephen Freeman has written over the years about how this passage is in agreement with what J.R.R. Tolkien wrote in a letter many centuries later:

Father Stephen Freeman has written over the years about how this passage is in agreement with what J.R.R. Tolkien wrote in a letter many centuries later:

“Actually I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’— though it contains (and in legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory” (Letters 255).

This narrative of a long defeat was assumed among ancient peoples, Fr. Stephen tells us, and only changed to one of progress in recent centuries, especially during the 19th century. But the defeat of history is not really pessimistic. It is part of the greater story of Christ’s Kingdom that has come, and is coming:

“I would go further and say that the final victory already “tabernacles” among us. It hovers within and over our world, shaping it and forming it, even within its defeat. For the nature of our salvation is a Defeat. Therefore the defeat within the world itself is not a tragic deviation from the end, but an End that was always foreseen and present within the Cross itself.”

The whole article is here: “Tolkien’s Long Defeat and the Path of History.”

The liturgical calendar doesn’t have much to do with that long defeat. You can go to any timeline of history to see the kingdoms that have risen and fallen, and the many wars and tribulations, the violence and suffering that have filled the earth since the beginning. Taken as a whole it’s hard to see any true progress there, unless you are talking about Wonder Bread or flush toilets.

No, the liturgical New Year begins the commemorations of Great Feasts of the Orthodox Church, following the sequence of events in what is sometimes called our Salvation History. The birth of Christ’s mother, the birth of Christ, the Presentation of Christ in the Temple, and so on. The death and resurrection of Christ are the peak season on that calendar. Christ’s defeat, and death — swallowed up in victory. That is cause to say “Christ is risen!” and “Happy New Year!” God is with us.

“Keeping the commandments of Christ is not doing nothing. It is, however, the refusal to use violence to force the world into ever-changing imaginary versions of the good.”

“Keeping the commandments of Christ is not doing nothing. It is, however, the refusal to use violence to force the world into ever-changing imaginary versions of the good.”

I came to the end of Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy, and feel that my engagement with the author and his theses has barely begun. The insights about eternal human longings down through the ages, and even small details about the lives of individual thinkers, will be rattling around in my mind for a long time to come, and I hope to refer to some of them in the future.

I came to the end of Irrational Man: A Study in Existential Philosophy, and feel that my engagement with the author and his theses has barely begun. The insights about eternal human longings down through the ages, and even small details about the lives of individual thinkers, will be rattling around in my mind for a long time to come, and I hope to refer to some of them in the future.

“If man is to be given meaning, the Existentialists have shown us, it must be here and now; and to think this insight through is to recast the whole tradition of Western thought. The realization that all human truth must not only shine against an enveloping darkness, but that such truth is even shot through with its own darkness may be depressing, and not only to utopians. But it has the virtue of restoring to man his sense of the primal mystery surrounding all things, a sense of mystery from which the glittering world of his technology estranges him, but without which he is not truly human.”

“If man is to be given meaning, the Existentialists have shown us, it must be here and now; and to think this insight through is to recast the whole tradition of Western thought. The realization that all human truth must not only shine against an enveloping darkness, but that such truth is even shot through with its own darkness may be depressing, and not only to utopians. But it has the virtue of restoring to man his sense of the primal mystery surrounding all things, a sense of mystery from which the glittering world of his technology estranges him, but without which he is not truly human.”