Palm Sunday is the beginning of Holy Week, and here on the eve of it I’m sharing again, slightly updated, my experience of about ten years ago when I was in the middle of reading The Brothers Karamazov, and I came to the the part “From the Life of the Elder Zosima,” which takes place during this week leading up to Christ’s death and resurrection:

The Elder Zosima first relates about his older brother, who only at the age of seventeen and sick unto death, turned from anger and scoffing toward a path that might lead to repentance, and seemingly only to please his mother. But that is not an entirely bad reason.

… on Tuesday morning my brother started keeping the fast and going to church. “I’m doing it only for your sake, mother, to give you joy and peace,” he said to her….But he did not go to church for long, he took to his bed, so that he had to confess and receive communion at home. The days grew bright, clear, fragrant — Easter was late that year. All night, I remember, he used to cough, slept badly, but in the morning he would always get dressed and try to sit in an armchair. So I remember him: he sits, quiet and meek, he smiles, he is sick but his countenance is glad, joyful. He was utterly changed in spirit — such a wondrous change had suddenly begun in him!

… on Tuesday morning my brother started keeping the fast and going to church. “I’m doing it only for your sake, mother, to give you joy and peace,” he said to her….But he did not go to church for long, he took to his bed, so that he had to confess and receive communion at home. The days grew bright, clear, fragrant — Easter was late that year. All night, I remember, he used to cough, slept badly, but in the morning he would always get dressed and try to sit in an armchair. So I remember him: he sits, quiet and meek, he smiles, he is sick but his countenance is glad, joyful. He was utterly changed in spirit — such a wondrous change had suddenly begun in him!

The young man asked forgiveness of everyone and talked about his great sin, but at the same time was so happy and full of thankfulness and exhortations, that people thought he was going mad.

Thus he awoke every day with more and more tenderness, rejoicing and all atremble with love. The doctor would come — the old German Eisenschmidt used to come to us: “Well, what do you think, doctor, shall I live one more day in the world?” he would joke with him. “Not just one day, you will live many days,” the doctor would answer, “you will live months and years, too.” “But what are years, what are months!” he would exclaim. “Why count the days, when even one day is enough for a man to know all happiness. My dears, why do we quarrel, boast before each other, remember each other’s offenses? Let us go into the garden, let us walk and play and love and praise and kiss each other, and bless our life.”

This older brother died a few weeks after Easter, when the teller of the story, the elder Zosima, was only eight years old. Now now near death himself, he talks more about his childhood, and how it was also during Holy Week that he began to see more when he went to church.

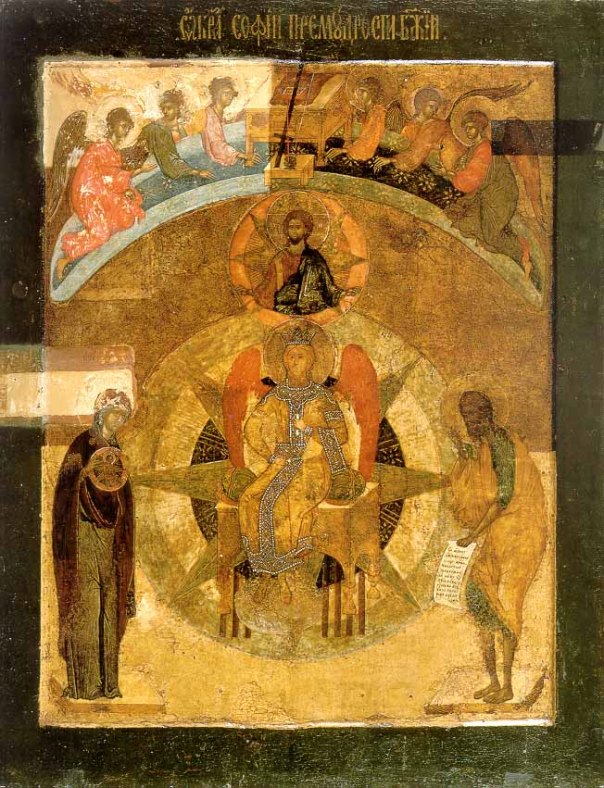

But I remember how, even before I learned to read, a certain spiritual perception visited me for the first time, when I was just eight years old. Mother took me to church by myself (I do not remember where my brother was then), during Holy Week, to the Monday liturgy. It was a clear day, and, remembering it now, I seem to see again the incense rising from the censer and quietly ascending upwards, and from above, through a narrow window in the cupola, God’s rays pouring down upon us in the church, and the incense rising up to them in waves, as if dissolving into them. I looked with deep tenderness, and for the first time in my life I consciously received the first seed of the word of God in my soul. A young man walked out into the middle of the church with a big book, so big that it seemed to me he even had difficulty in carrying it, and he placed it on the analogion [lectern], opened it, and began to read, and suddenly, then, for the first time I understood something, for the first time in my life I understood what was read in God’s church.

The reading was from the book of Job. I myself have attended these same services over the years, and they grow more precious every time I hear the readings and hymns. The gifts of the Church are too rich to ever plumb their depths, but there is no need to fret about our limitations, when, as the sick brother says, “even one day is enough for a man to know all happiness.” How many times have I also watched the beams of light shining down when I stood in church, and even felt their heat on my face, like the warmth of God’s love?

The Elder Zosima is a fictional character, but he is believed to be based on a real-life monk in old Russia. In the novel the Elder proceeds from this point in his very moving fashion to tell his life’s story: “– and over all is God’s truth, moving, reconciling, all-forgiving!”

The “accidental” timing of my reading seemed to be a gift from God that morning, helping me in an unusual way to become even more receptive to His being with us at the evening service by means of hymns such as, “Let my prayer arise in Thy sight as incense….,” and the Psalms of Ascent — and the Holy Mysteries.

When our bishop was with us the previous week, he gave a good word about the last days of Lent — well, technically Lent has come to an end, but we are still in the anticipation and preparation that is Holy Week. He said that Lent is not about finding every bit of dirt in our souls, but about the bridal chamber, about discovering the great love that our Lord Jesus has for us. It is truly a “bright sadness” that colors these days as we accompany Him to the Cross.

Perhaps Zosima’s brother went to a Bridegroom Matins service on Tuesday; we have three of them during Holy Week. The Lord Himself has been filling my lamp with the oil of His Holy Spirit.

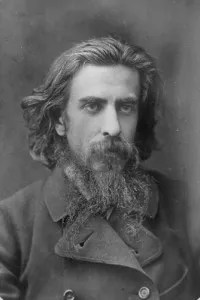

On this day we remember St. Tikhon of Zadonsk, a man born into a poor Russian family in 1724. He excelled in school, and after attending seminary became a teacher, and then a monk. After being elevated to the bishopric, at one time he had over 800 churches under his care; the story of his life is well told:

On this day we remember St. Tikhon of Zadonsk, a man born into a poor Russian family in 1724. He excelled in school, and after attending seminary became a teacher, and then a monk. After being elevated to the bishopric, at one time he had over 800 churches under his care; the story of his life is well told: