I am re-posting this book review because even I who wrote it am fascinated all over again when I consider the character and the story. I’m sure many of my readers have not read all the book reports I’ve made, and some of you who read this review the first time might not have been interested back then. I might need a reread of Peony myself.

I am re-posting this book review because even I who wrote it am fascinated all over again when I consider the character and the story. I’m sure many of my readers have not read all the book reports I’ve made, and some of you who read this review the first time might not have been interested back then. I might need a reread of Peony myself.

I am so blessed to have met the appealing character of Peony in Pearl S. Buck’s novel about Jews in China. It seems that as early as the 8th century Jewish traders settled in China and their tribe increased through the centuries. Buck thoroughly researched their history and includes many authentic details in this story that tells about their community in the city of K’aifeng in the northern province of Honan. She gives a short intro and timeline of the Jewish presence in China in a preface, and my Kindle edition includes an afterword by Wendy R. Abraham with a thorough history up to about 1990.

The events take place in the middle of the 19th century. At this time the last rabbi died and the Jews were in the final stages of being assimilated into the Chinese culture. One big reason can be summed up in this question that several of the characters ask themselves: “…here [in China], where all are friends to us and receive us eagerly into their blood, what is the reward for remaining apart?”

The story is told from the point of view of the Chinese bondmaid Peony, who belongs to a Jewish household and for her own survival uses all her resources to promote this abandonment of her owners’ practice of their Jewish lifestyle. She and the Young Master of the household grew up as playmates and good friends, and now that they have come of age she works to turn his heart away from the faith that has been passed down from his parents. That may sound bad, but she is honestly playing her part in this drama in which each one tries to follow the most prudent path he can, while at the same time honoring his elders. From the distance of time or in a novel we can see a broad view, but when you are thrust into a role with no script, you can only do your best.

The substance of the Jewish faith portrayed in the novel is somewhat vague. Other than the goals of “remaining separate” and remembering their history, any tenets of faith mentioned were ideas the Chinese neighbors could and did easily agree with. An example of this is in a synagogue mentioned in the story, on whose stones are written “‘The Temple of Purity and Truth,’ and beneath the words are carved the history of the Jews and their Way, and it is there said, ‘The Way has no form or figure, but is made in the image of the Way of Heaven, which is above.'”

The name of the temple is factual, and if the confusing statement about The Way comes from Pearl Buck’s imagination, it is probably based on the truth of what it is like to try to live out a faith tradition that is more history than reality. This experience — or rather, lack of it — is certainly not foreign to many moderns.

I don’t know when I last read such a wonderful work of fiction. It was a page-turner because I could not at all imagine how the plot would flow. The setting in China was the primary strange aspect for me; I don’t think I’ve read any of Buck’s other works set in that country and I’ve been fairly incurious about Asia generally. But recent exposure to the writings of Lin Yutang has made the history and culture of China seem much more accessible and intriguing, and prepared me to enter into this tale.

Peony is a young Chinese girl whose depiction I fully trust, because Pearl S. Buck grew up in China as the daughter of Presbyterian missionaries and was immersed in that world. She returned as an adult and wrote many books about China and its people, including the most famous one, The Good Earth. Lin Yutang himself was a friend of hers and they seem to have encouraged each other in their writing.

Peony was sold by her mother to the family whom she serves; she has no one else but them in the world. So she sees that it is in her interest to be the very best servant she can be, and she truly loves not only the Young Master but his parents. About the Young Master she thinks, “His heart was centered in himself, and so must hers be centered in him.”

Her love for the family increases as the years go by, even as they come to depend on her in countless ways. That’s o.k., because she always tries to make things work out for their health and welfare. Her own happiness must be found in the context of disappointment, and in relationship with people who take her for granted.

When she is still fairly young she asks the older servant a philosophical question:

Was life sad or happy? She did not mean her life or any one life, but life itself— was it sad or happy? If she but had the answer to that first question, Peony thought, then she would have her guide. If life could and should be happy, if to be alive itself was good, then why should she not try for everything that could be hers? But if, when all was won, life itself was sad, then she must content herself with what she had.

“You cannot be happy until you understand that life is sad,” Wang Ma declared. “See me, Little Sister! What dreams I made and how I hoped before I knew that life is sad! After I understood this truth I made no more dreams. I hoped no more. Now I am often happy, because some good things come to me. Expecting nothing, I am glad for anything.”

Getting to know Peony and watching how she matures over the years was pure pleasure. She has good sense and character even as a teenager, and as she responds to the sometimes cataclysmic changes in the household her competence and wisdom grow, often through struggling to overcome her own desires and heartache. Through her we get an idea of how the Jewish religious practices might have appeared to the Chinese, and she also epitomizes many of the best qualities of the Chinese and their outlook on life that I was only recently reading about in Lin Yutang’s books.

For me the Jewish characters in the story were also unpredictable, though they are well-drawn and believable. They are people of their particular time and place, most of them already a unique blend of the Chinese and Hebrew. The patriarch of the family is of mixed-blood, having had the “consolation” of “a rosy, warm little Chinese mother.” This image is contrasted with his own wife who is almost single-handedly trying to preserve their religious tradition, and who causes a Jewish friend to muse, “For a woman to love God too much was not well, he now told himself. She must not love God more than man, for then she made herself man’s conscience, and he was the pursued.”

This theme of women and their power is another element of the story that fascinated me, being myself a woman with power. Of the only son David we read,

His mother, Leah, Peony, Kueilan, these four women who had somehow between them shaped his life were shaping him still. He longed to be free of them all, and yet he knew that no man is ever free of the women who have made him what he is. He sighed and tossed and wished for the day when he could return to the shops and the men there who had nothing to do with his heart and his soul.

In the end it is Peony who has the best and sweetest sort of influence. Her conversation with the father when she is giving him a foot-rub:

Peony knew his thoughts. Nevertheless, she asked, “Why do you sigh, Master?” “Because I do not know what is right,” Ezra replied. She laughed softly at this. “You are always talking of right and wrong,” she said. Now she was pressing the soles of his feet. They were hard and broad, but supple. She went on in her cheerful way. “Yet what is right except that which makes happiness and what is wrong except that which makes sorrow?” “You speak so because you are not confused between Heaven and earth,” he said. “I know I belong to earth,” she said simply.

I’ve tried not to spoil the story by telling too much. One review I read ahead of time said something about the ending being sad, but I didn’t find it so. We find Peony considering her life and that of the people she has served, and wondering if she had been wrong to have a part in closing the book on the Jewish tradition in her city. In keeping with her outlook on life and religion, she concludes that it’s all o.k.:

Long she pondered, and as often happened to her in her great age, the answer came to her. She had not done wrong, for nothing was lost. “Nothing is lost,” she repeated. “[The Jew] lives again and again, among our people,” she mused. “Where there is a bolder brow, a brighter eye, there is one like him; where a voice sings most clearly, there is one; where a line is drawn most cleverly to make a picture clear, a carving strong, there is one; where a statesman stands most honorable, a judge most just, there is one; where a scholar is most learned, there is one; where a woman is both beautiful and wise, there is one. Their blood is lively in whatever frame it flows, and when the frame is gone, its very dust enriches the still kindly soil.”

It’s been ten years since I posted this review. Since then I have revisited the story itself, and it seemed good to publish again. It’s well worth sharing at least that often.

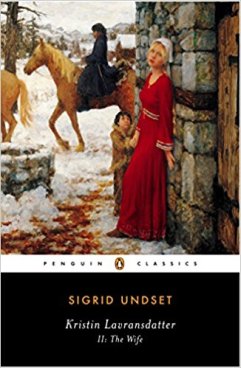

It’s been ten years since I posted this review. Since then I have revisited the story itself, and it seemed good to publish again. It’s well worth sharing at least that often.  d with medieval Norway, or at least, that I didn’t want to spend time on a third reading when there are so many other books still to be known. That feeling didn’t last long, because by the time I came to the last pages I knew that I still have a lot to gain from acquaintance with the themes in this amazing epic by Sigrid Undset. It’s a glory to God that one human mind can create a complex and rich world like that of Kristin, peopled with characters whose drama reflects our own struggles to love God and repent of our besetting sins. Image Journal included the novel in its list of 100 best books of the 20th century that “manifest a genuine engagement with the Judeo-Christian heritage of faith.”

d with medieval Norway, or at least, that I didn’t want to spend time on a third reading when there are so many other books still to be known. That feeling didn’t last long, because by the time I came to the last pages I knew that I still have a lot to gain from acquaintance with the themes in this amazing epic by Sigrid Undset. It’s a glory to God that one human mind can create a complex and rich world like that of Kristin, peopled with characters whose drama reflects our own struggles to love God and repent of our besetting sins. Image Journal included the novel in its list of 100 best books of the 20th century that “manifest a genuine engagement with the Judeo-Christian heritage of faith.”

me at the perfect time. I know Who does it, and so does Mrs. Bread, but I bet even she is surprised to find how long it took Him to arrange this one by means of my constantly re-jumbling the jumble.

me at the perfect time. I know Who does it, and so does Mrs. Bread, but I bet even she is surprised to find how long it took Him to arrange this one by means of my constantly re-jumbling the jumble.

haven’t been able to concentrate on this extended philosophical reading project. It could be also that the topic is just too out-of-sync with the situation in my (indoor) living space. The chaos results from having none of the planned-for storage finished — that’s closets and cabinets in six or seven rooms — and that situation is abetted by the pandemic shutdowns of various sorts. The pandemic itself taxes the mind and emotions, and lately I’ve been reading more children’s books than anything.

haven’t been able to concentrate on this extended philosophical reading project. It could be also that the topic is just too out-of-sync with the situation in my (indoor) living space. The chaos results from having none of the planned-for storage finished — that’s closets and cabinets in six or seven rooms — and that situation is abetted by the pandemic shutdowns of various sorts. The pandemic itself taxes the mind and emotions, and lately I’ve been reading more children’s books than anything.

But, going back to the beginning of my vague plan, about a year ago I brought a fat book about Beauty and Truth into the house. The priest who lent it to me said he’d been unable to penetrate it. I knew it would likely be as heavy for me intellectually as it was in poundage, but it seemed a work I should at least have at hand when I began my study of Beauty.

But, going back to the beginning of my vague plan, about a year ago I brought a fat book about Beauty and Truth into the house. The priest who lent it to me said he’d been unable to penetrate it. I knew it would likely be as heavy for me intellectually as it was in poundage, but it seemed a work I should at least have at hand when I began my study of Beauty.