I relate to this woman:

UNTITLED

A beast in winter,

a plant in spring,

an insect in summer,

a bird in autumn.

The rest of the time I am a woman.

-Vera Pavlova

I relate to this woman:

UNTITLED

A beast in winter,

a plant in spring,

an insect in summer,

a bird in autumn.

The rest of the time I am a woman.

-Vera Pavlova

It’s been a long time since I read Mark Twain’s Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc. When I came across the quote below it made me want to read it again — though I can see the good in reading a different biographer.

The Scholé Sisters presented again their idea of the 5×5 reading plan. You pick five topics or genres of books and try to read five books in each category. Personally, I won’t be officially joining the group challenge, but this organizing of my stacks does sound appealing. Already “Women” was one of the categories that immediately came to my mind, and a book about Joan of Arc would fit very nicely. I wish Chesterton had written one; this is from his book Orthodoxy:

“Joan of Arc was not stuck at the Cross Roads either by rejecting all the paths like Tolstoy or by accepting them all like Nietzsche. She chose a path and went down it like a thunderbolt. Yet Joan, when I come to think of her, had in her all that was true either in Tolstoy or Nietzsche — all that was even tolerable in either of them.

“I thought of all that is noble in Tolstoy: the pleasure in plain things, especially in plain pity, the actualities of the earth, the reverence for the poor, the dignity of the bowed back. Joan of Arc had all that, and with this great addition: that she endured poverty while she admired it, whereas Tolstoy is only a typical aristocrat trying to find out its secret.

“And then I thought of all that was brave and proud and pathetic in poor Nietzsche and his mutiny against the emptiness and timidity of our time. I thought of his cry for the ecstatic equilibrium of danger, his hunger for the rush of great horses, his cry to arms. Well, Joan of Arc had all that and, again, with this difference, that she did not praise fighting, but fought. We know that she was not afraid of an army, while Nietzsche for all we know was afraid of a cow.

“Tolstoy only praised the peasant; she was the peasant. Nietzsche only praised the warrior; she was the warrior. She beat them both at their own antagonistic ideals; she was more gentle than the one, more violent than the other. Yet she was a perfectly practical person who did something, while they are wild speculators who do nothing.”

G.K. Chesterton, in Orthodoxy

“I know that I am treading on tender ground; but I cannot help thinking that the restless pains we take to cram up every little vacuity of life, by crowding one new thing upon another, rather creates a thirst for novelty than knowledge; and is but a well-disguised contrivance to keep us in after-life more effectually from conversing with ourselves.

“I know that I am treading on tender ground; but I cannot help thinking that the restless pains we take to cram up every little vacuity of life, by crowding one new thing upon another, rather creates a thirst for novelty than knowledge; and is but a well-disguised contrivance to keep us in after-life more effectually from conversing with ourselves.

“The care taken to prevent ennui is but a creditable plan for promoting self-ignorance. We run from one occupation to another (I speak of those arts to which little intellect is applied) with a view to lighten the pressure of time; above all to save us from our own thoughts; whereas, were we thrown a little more on our own hands, we might at last be driven, by way of something to do, to try to get acquainted with our own hearts; and though our being less absorbed by this busy trifling and frivolous hurry, might render us somewhat more sensible of the taedium of life, might not this very sensation tend to quicken our pursuit of a better?”

— Hannah More, Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education, 1799

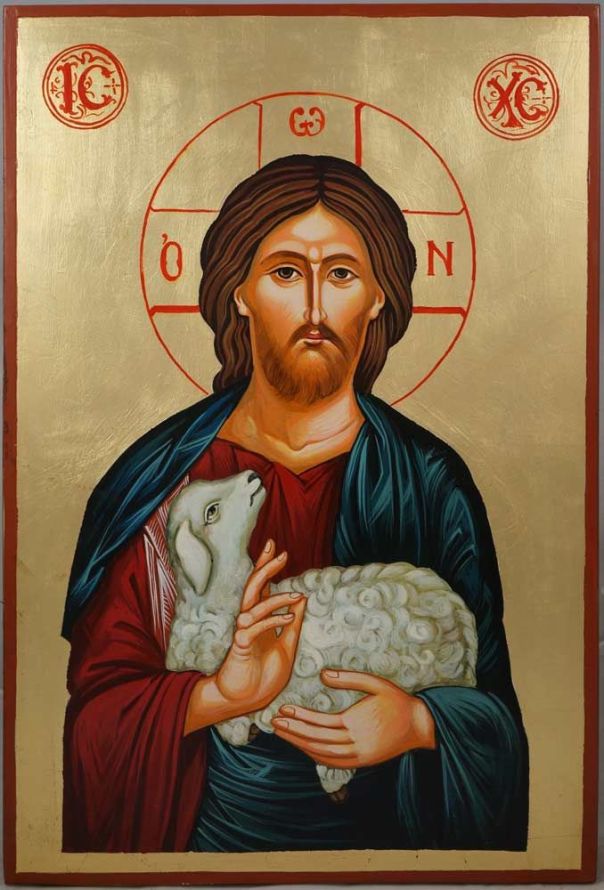

THE TEN DRACHMAS:

The Lord in the Guise of a Woman

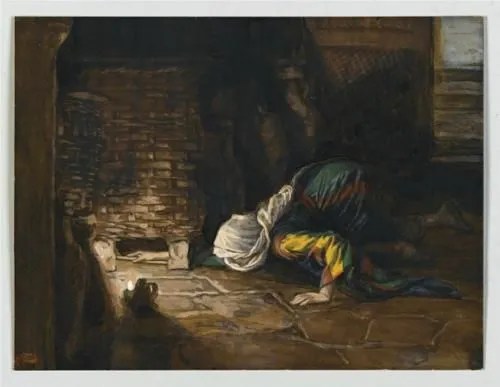

“Can you believe that Christ the Saviour portrayed Himself in the guise of a woman in two of His parables? One is that of the woman who took three measures of flour and made dough. But first let us speak of the other one where the Lord tells us about the woman who had ten drachmas and lost one. These are the most mysterious of all the Saviour’s parables. As the parable of the lost drachma is short, we quote it in full.”

“Or what woman, having ten drachmas, if she lose one, does not light a candle and sweep the house and look diligently till she finds it? And after she has found it, she calls in her friends and neighbors and says, Rejoice with me, for I have found the drachma that I lost (Luke 15:8-9).”

“At first glance this parable seems so simple, or even naive, that it does not impress the reader of the Gospel. In fact, however, the mystery of the universe is revealed in this simple parable.”

The paragraphs above are the first part of an article by St. Nikolai Velimirovich, which I’m happy to bring to your attention. From his statement about the mystery of the universe, the author goes on to point out the puzzling elements in this very short story, and to explain two interpretations, both of which he says are correct. I will let you read the whole exposition at your leisure: “The Ten Drachmas” (in which he also treats the second story, the “Three Measures of Flour,” in detail). But I want to share one more excerpt, which returns to the question of why the protagonist in “The Ten Drachmas” must be a woman:

“Our Lord described Himself as a woman because women are more careful than men in  looking after property, in keeping the house in order and in receiving guests. If this short parable, which consists of only two sentences, is explained in this way, whose heart will not tremble? for it contains the whole tragedy of the world, visible and invisible. It explains why the Son of God came to earth. It sheds a bright ray of light on the history of mankind and the tragedy of each individual’s existence.

looking after property, in keeping the house in order and in receiving guests. If this short parable, which consists of only two sentences, is explained in this way, whose heart will not tremble? for it contains the whole tragedy of the world, visible and invisible. It explains why the Son of God came to earth. It sheds a bright ray of light on the history of mankind and the tragedy of each individual’s existence.

“It confronts us with an urgent decision, because our life is swiftly passing — a decision as to whether we want to be the lost drachma found by Christ or not. Christ is looking for us. Are we going to hide from him, or let ourselves be found by Him before death hides us from Him, from the world and from life?”

-St. Nikolai Velimirovich