Psalm 58:8

Thou tellest my wanderings:

put thou my tears into thy bottle:

are they not in thy book?

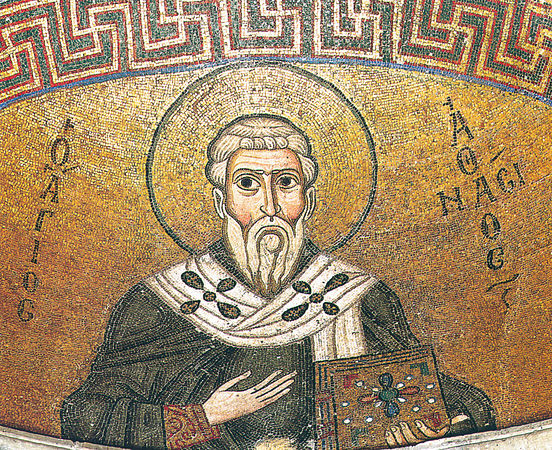

The more one researches current events, historical accounts, and the tangled web of cultures  and civilizations going back to the foundation of the world, the more likely is a fall into worry and even despair. We fear especially for children who have to grow up in a violent era, as many have done. That’s why I take courage from the life of St. Athanasius, and pray that my children, grandchildren, godchildren, and all of us, might learn deep in our souls what he knew. The following is an excerpt from a post I wrote several years ago in a time of sorrow. I have shared the quote from his treatise more recently than that, but I hope you might agree with me that it’s worth rereading:

and civilizations going back to the foundation of the world, the more likely is a fall into worry and even despair. We fear especially for children who have to grow up in a violent era, as many have done. That’s why I take courage from the life of St. Athanasius, and pray that my children, grandchildren, godchildren, and all of us, might learn deep in our souls what he knew. The following is an excerpt from a post I wrote several years ago in a time of sorrow. I have shared the quote from his treatise more recently than that, but I hope you might agree with me that it’s worth rereading:

![]()

I learned in the short account of the life of Athanasius at the beginning of his On the Incarnation, that the last and worst persecution of Christians ended in Egypt in 311 A.D., when Athanasius was about fourteen. From the age of five he had lived with the constant threat of death, and with the ever-present reality of persecution of his friends and family. The behavior of the ungodly is irrational and inhuman, and tends to cause great pain and suffering, often unto death, not only of the innocent but also of the most Christ-like. As an adult the scenes and events of his childhood seem to be fresh in his mind when he writes:

“A very strong proof of this destruction of death and its conquest by the cross is supplied by the present fact, namely this. All the disciples of Christ despise death; they take the offensive against it and instead of fearing it, by the sign of the cross and by faith in Christ trample on it as on something dead. Before the divine sojourn of the Saviour, even the holiest of men were afraid of death, and mourned the dead as those who perish. But now that the Saviour has raised his body, death is no longer terrible, but all those who believe in Christ tread it underfoot as nothing, knowing full well that when they die they do not perish, but live indeed, and become incorruptible through the resurrection. But that devil who of old wickedly exulted in death, now that the pains of death are loosed, he alone it is who remains truly dead.”

“Keeping the commandments of Christ is not doing nothing. It is, however, the refusal to use violence to force the world into ever-changing imaginary versions of the good.”

“Keeping the commandments of Christ is not doing nothing. It is, however, the refusal to use violence to force the world into ever-changing imaginary versions of the good.”